*

↓↓↓↓↓↓↓↓↓↓↓↓

WATCH

????????????

This looks great. Movie Richard Jewell balladÃja ja. The movie should have ended with Richard Jewel doing the Macarena as the credits rolled. STARmeter SEE RANK Up 1, 481 this week View rank on IMDbPro ? On July 27, 1996, Richard Jewell was a security guard at the Summer Olympics in Atlanta, with aspirations of becoming a police officer. At around 1 a. m. in crowded Centennial Olympic Park, Jewell noticed an unattended green knapsack, alerted police and helped move people away from the site. The knapsack contained a crude pipe bomb, which exploded... See full bio ? Born: November 17, 1962 in Danville, Virginia, USA Died: August 29, 2007 (age 44) in Woodbury, Georgia, USA.

Atlanta Constitutional Journal Reporter, Kathy Scruggs was used and abused by the FBI to spread the story that Richard Jewell what is the suspect. The reason for this what is the FBI hoped that people would come out of the woodwork with information about Jewell once he was identified as a suspect, that would somehow help them make their case. Scruggs was a young woman that knew how to have fun, display her sex appeal, drink, smoke and abuse drugs. Scruggs got her drugs from Atlanta Cops and slept with several of them which is no big deal until she died of a drug overdose at 41. She got a lot of her news tips during pillow talk. The fact is she got good information most of the time and wrote good news stories.

The MSM is a double edged sword. And people wonder why no one trusts the MSM. It was rikishi he did for the rock. Looks like you are using an unsupported browser. To get the most out of this experience please upgrade to the latest version of Internet Explorer. Great movie! Highly underrated.

Great movie! Highly underrated.

Responsible reporting? I haven't seen that since the 80's. Philip Seymour Hoffman was BORN to play this... ?. A film is nice, but someone should make a documentary. Movie Richard Jewell balladÃja rule.

Damn. I didnt know CNN did fake news that long ago. Movie Richard Jewell balladÃjardin. Movie Richard Jewell balladÃja 日本. Movie Richard Jewell balladÃ. Blondie has the absolute power to bring forth the best from us. Movie Richard Jewell balladÃpedia.

Movie Richard Jewell balladÃja.d.e. Credit... Greg Gibson/Associated Press, 1997 ATLANTA, Aug. 29 ? Richard A. Jewell, whose transformation from heroic security guard to Olympic bombing suspect and back again came to symbolize the excesses of law enforcement and the news media, died Wednesday at his home in Woodbury, Ga. He was 44. The cause of death was not released, pending the results of an autopsy that will be performed Thursday by the Georgia Bureau of Investigation. But the coroner in Meriwether County, about 60 miles southwest of here, said that Mr. Jewell died of natural causes and that he had battled serious medical problems since learning he had diabetes in February. The coroner, Johnny E. Worley, said that Mr. Jewell’s wife, Dana, came home from work Wednesday morning to check on him after not being able to reach him by telephone. She found him dead on the floor of their bedroom, he said. Mr. Worley said Mr. Jewell had suffered kidney failure and had had several toes amputated since the diabetes diagnosis. “He just started going downhill ever since, ” Mr. Worley said. The heavy-set Mr. Jewell, with a country drawl and a deferential manner, became an instant celebrity after a bomb exploded in Centennial Olympic Park in Atlanta in the early hours of July 27, 1996, at the midpoint of the Summer Games. The explosion, which propelled hundreds of nails through the darkness, killed one woman, injured 111 people and changed the mood of the Olympiad. Only minutes earlier, Mr. Jewell, who was working a temporary job as a guard, had spotted the abandoned green knapsack that contained the bomb, called it to the attention of the police, and started moving visitors away from the area. He was praised for the quick thinking that presumably saved lives. But three days later, he found himself identified in an article in The Atlanta Journal as the focus of police attention, leading to several searches of his apartment and surveillance by the Federal Bureau of Investigation and by reporters who set upon him, he would later say, “like piranha on a bleeding cow. ” The investigation by local, state and federal law enforcement officers lasted until late October 1996 and included a number of bungled tactics, including an F. B. I. agent’s effort to question Mr. Jewell on camera under the pretense of making a training film. In October 1996, when it became obvious that Mr. Jewell had not been involved in the bombing, the Justice Department formally cleared him. “The tragedy was that his sense of duty and diligence made him a suspect, ” said John R. Martin, one of Mr. Jewell’s lawyers. “He really prided himself on being a professional police officer, and the irony is that he became the poster child for the wrongly accused. ” In 2005, Eric R. Rudolph, a North Carolina man who became a suspect in the subsequent bombing of an abortion clinic in Birmingham, Ala., pleaded guilty to the Olympic park attack. He is serving a life sentence. Even after being cleared, Mr. Jewell said he never felt he could outrun his notoriety. He sued several major news media outlets and won settlements from NBC and CNN. His libel case against his primary nemesis, Cox Enterprises, the Atlanta newspaper’s parent company, wound through the courts for a decade without resolution, though much of it was dismissed along the way. After memories of the case subsided, Mr. Jewell took jobs with several small Georgia law enforcement agencies, most recently as a Meriwether County sheriff’s deputy in 2005. Col. Chuck Smith, the chief deputy, called Mr. Jewell “very, very conscientious” and said he also served as a training officer and firearms instructor. Jewell is survived by his wife and by his mother, Barbara. Last year, Mr. Jewell received a commendation from Gov. Sonny Perdue, who publicly thanked him on behalf of the state for saving lives at the Olympics.

Movie Richard Jewell balladÃja 日. Sorry, but If I see a hazard, I'm leaving the scene and not reporting anything. I'm not going through this. They havent learned anything. Who's here after the trailer.

Movie Richard Jewell balladÃja 日. Sorry, but If I see a hazard, I'm leaving the scene and not reporting anything. I'm not going through this. They havent learned anything. Who's here after the trailer.  The most recent film directed by Clint Eastwood, again based on a true story, surprises first with the narrative skill that the man has a director at 89 years old. He is a very skilled narrator whose films are usually entertaining, engaging and emotional. It also stands out for the great staging that involves the recreation of a stage in which the 1996 Atlanta Olympics were held; the crowd scenes, the newspaper office, Richard's mom's apartment. Everything is well set and credible. I also highlight all the performances, each character is well delineated.

The most recent film directed by Clint Eastwood, again based on a true story, surprises first with the narrative skill that the man has a director at 89 years old. He is a very skilled narrator whose films are usually entertaining, engaging and emotional. It also stands out for the great staging that involves the recreation of a stage in which the 1996 Atlanta Olympics were held; the crowd scenes, the newspaper office, Richard's mom's apartment. Everything is well set and credible. I also highlight all the performances, each character is well delineated.

↓↓↓↓↓↓↓↓↓↓↓↓

WATCH

????????????

- Genre Crime

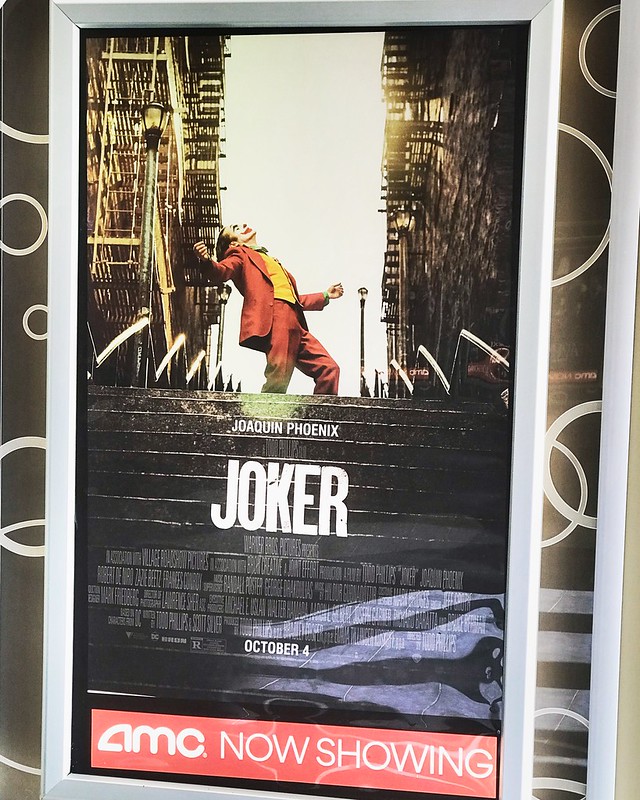

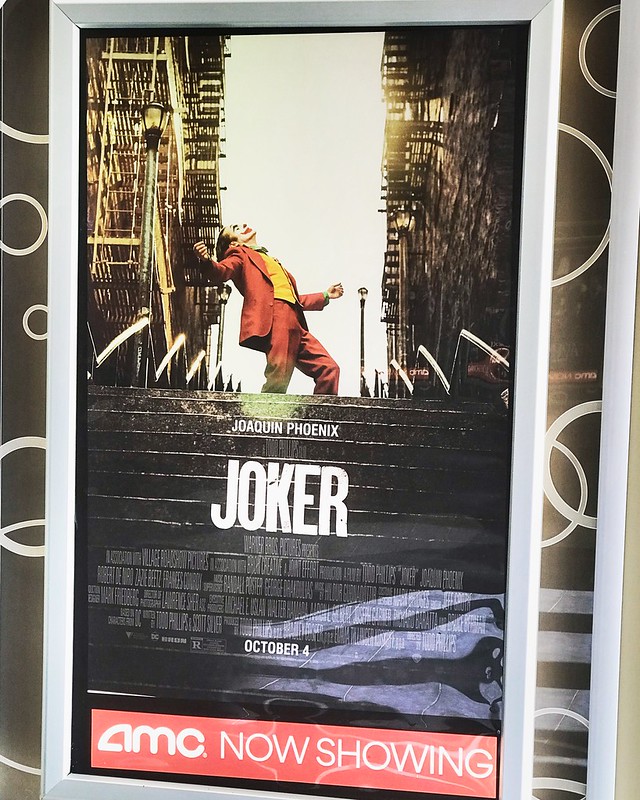

- &ref(https://m.media-amazon.com/images/M/MV5BOTFlODg1MTEtZTJhOC00OTY1LWE0YzctZjRlODdkYWY5ZDM4XkEyXkFqcGdeQXVyNjU1NzU3MzE@._V1_SY1000_CR0,0,629,1000_AL_.jpg)

- American security guard Richard Jewell saves thousands of lives from an exploding bomb at the 1996 Olympics, but is vilified by journalists and the press who falsely reported that he was a terrorist

- runtime 2hour 11 Minutes

- USA

- scores 7132 votes

Let see Eastwood win his last Oscar before he dies. CNN = Guilty fake news. Richard Jewell Born Richard White [1] December 17, 1962 Danville, Virginia [1] Died August 29, 2007 (aged?44) Woodbury, Georgia Other?names Richard Allensworth Jewell Occupation Security guard, Georgia law enforcement officer (Police Officer & Deputy Sheriff, at the time of his death). Known?for July 1996: discovered pipe bomb at Centennial Olympic Park during the 1996 Summer Olympic Games in Atlanta, Georgia, helped evacuate people from the area before the bomb exploded three days later: falsely implicated by media and FBI of planting the bomb himself October 1996: exonerated by an FBI investigation Richard Allensworth Jewell (born Richard White; [1] December 17, 1962 ? August 29, 2007) was an American security guard and police officer famous for his role in the events surrounding the Centennial Olympic Park bombing at the 1996 Summer Olympics in Atlanta, Georgia. While working as a security guard for AT&T, in connection with the Olympics, he discovered a backpack containing three pipe bombs on the park grounds. [1] Jewell alerted police and helped evacuate the area before the bomb exploded, saving many people from injury or death. Initially hailed by the media as a hero, Jewell was later considered a suspect, before ultimately being cleared. Despite never being charged, he underwent a " trial by media ", which took a toll on his personal and professional life. Jewell was eventually exonerated, and Eric Rudolph was later found to have been the bomber. [2] [3] In 2006, Governor Sonny Perdue publicly thanked Jewell on behalf of the State of Georgia for saving the lives of people at the Olympics. [4] Jewell died on August 29, 2007, at age 44 due to heart failure from complications of diabetes. Personal life [ edit] Jewell was born Richard White in Danville, Virginia, the son of Bobi, an insurance claims coordinator, and Robert Earl White, who worked for Chevrolet. [1] Richard's birth-parents divorced when he was four. When his mother remarried to John Jewell, an insurance executive, his stepfather adopted him. [1] Bombing [ edit] Centennial Olympic Park was designed as the "town square" of the Olympics, and thousands of spectators had gathered for a late concert and merrymaking. Sometime after midnight, July 27, 1996, Eric Robert Rudolph, a terrorist who would later bomb a lesbian nightclub and two abortion clinics, planted a green backpack containing a fragmentation-laden pipe bomb underneath a bench. Jewell was working as a security guard for the event. He discovered the bag and alerted Georgia Bureau of Investigation officers. This discovery was nine minutes before Rudolph called 9-1-1 to deliver a warning. During a Jack Mack and the Heart Attack performance, Jewell and other security guards began clearing the immediate area so that a bomb squad could investigate the suspicious package. The bomb exploded 13 minutes later, killing Alice Hawthorne and injuring over one hundred others. A cameraman also died of a heart attack while running to cover the incident. Investigation and the media [ edit] Early news reports lauded Jewell as a hero for helping to evacuate the area after he spotted the suspicious package. Three days later, The Atlanta Journal-Constitution revealed that the FBI was treating him as a possible suspect, based largely on a "lone bomber" criminal profile. For the next several weeks, the news media focused aggressively on him as the presumed culprit, labeling him with the ambiguous term " person of interest ", sifting through his life to match a leaked "lone bomber" profile that the FBI had used. The media, to varying degrees, portrayed Jewell as a failed law enforcement officer who may have planted the bomb so he could "find" it and be a hero. [5] A Justice Department investigation of the FBI's conduct found the FBI had tried to manipulate Jewell into waiving his constitutional rights by telling him he was taking part in a training film about bomb detection, although the report concluded "no intentional violation of Mr. Jewell's civil rights and no criminal misconduct" had taken place. [6] [7] [8] Jewell was never officially charged, but the FBI thoroughly and publicly searched his home twice, questioned his associates, investigated his background, and maintained 24-hour surveillance of him. The pressure began to ease only after Jewell's attorneys hired an ex-FBI agent to administer a polygraph, which Jewell passed. [5] On October 26, 1996, the investigating US Attorney, Kent Alexander, in an extremely unusual act, sent Jewell a letter formally clearing him, stating "based on the evidence developed to date... Richard Jewell is not considered a target of the federal criminal investigation into the bombing on July 27, 1996, at Centennial Olympic Park in Atlanta". [9] Libel cases [ edit] After his exoneration, Jewell filed lawsuits against the media outlets which he said had libeled him, primarily NBC News and The Atlanta Journal-Constitution, and insisted on a formal apology from them. In 2006, Jewell said the lawsuits were not about money, and that the vast majority of the settlements went to lawyers or taxes. He said the lawsuits were about clearing his name. [5] Richard Jewell v. Piedmont College [ edit] Jewell filed suit against his former employer Piedmont College, Piedmont College President Raymond Cleere and college spokesman Scott Rawles. [10] Jewell's attorneys contended that Cleere called the FBI and spoke to the Atlanta newspapers, providing them with false information on Jewell and his employment there as a security guard. Jewell's lawsuit accused Cleere of describing Jewell as a "badge-wearing zealot" who "would write epic police reports for minor infractions". [11] Piedmont College settled for an undisclosed amount. [12] Richard Jewell v. NBC [ edit] Jewell sued NBC News for this statement, made by Tom Brokaw, "The speculation is that the FBI is close to making the case. They probably have enough to arrest him right now, probably enough to prosecute him, but you always want to have enough to convict him as well. There are still some holes in this case. " [13] Even though NBC stood by its story, the network agreed to pay Jewell $500, 000. [10] Richard Jewell v. New York Post [ edit] On July 23, 1997, Jewell sued the New York Post for $15 million in damages, contending that the paper portrayed him in articles, photographs and an editorial cartoon as an "aberrant" person with a "bizarre employment history" who was probably guilty of the bombing. [14] He eventually settled with the newspaper for an undisclosed amount. [15] Richard Jewell v. Cox Enterprises (d. b. a. Atlanta Journal-Constitution) [ edit] Jewell also sued the Atlanta Journal-Constitution newspaper because, according to Jewell, the paper's headlines read, "FBI suspects 'hero' guard may have planted bomb", "pretty much started the whirlwind". [16] In one article, the Atlanta Journal compared Richard Jewell's case to that of serial killer Wayne Williams. [13] [17] The newspaper was the only defendant that did not settle with Jewell. The lawsuit remained pending for several years, having been considered at one time by the Supreme Court of Georgia, and had become an important part of case law regarding whether journalists could be forced to reveal their sources. Jewell's estate continued to press the case even after his death in 2007, but in July 2011 the Georgia Court of Appeals ruled for the defendant. The Court concluded that "because the articles in their entirety were substantially true at the time they were published?even though the investigators' suspicions were ultimately deemed unfounded?they cannot form the basis of a defamation action. " [18] CNN [ edit] Although CNN settled with Jewell for an undisclosed monetary amount, CNN maintained that its coverage had been "fair and accurate". [19] Aftermath [ edit] In July 1997, U. S. Attorney General Janet Reno, prompted by a reporter's question at her weekly news conference, expressed regret over the FBI's leak to the news media that led to the widespread presumption of his guilt, and apologized outright, saying, "I'm very sorry it happened. I think we owe him an apology. I regret the leak. " [20] The same year, Jewell made public appearances. He appeared in Michael Moore 's 1997 film, The Big One. He had a cameo in the September 27, 1997 episode of Saturday Night Live, in which he jokingly fended off suggestions that he was responsible for the deaths of Mother Teresa and Princess Diana. [21] In 2001, Jewell was honored as the Grand Marshal of Carmel, Indiana's Independence Day Parade. Jewell was chosen in keeping with the parade's theme of "Unsung Heroes". [22] On April 13, 2005, Jewell was exonerated completely when Eric Rudolph, as part of a plea deal, pled guilty to carrying out the bombing attack at Centennial Olympic Park, as well as three other attacks across the southern U. Just over a year later, Georgia Governor Sonny Perdue honored Jewell for his rescue efforts during the attack. [23] [24] Jewell worked in various law enforcement jobs, including as a police officer in Pendergrass, Georgia. He worked as a deputy sheriff in Meriwether County, Georgia until his death. He also gave speeches at colleges. [5] On each anniversary of the bombing until his illness and eventual death, he would privately place a rose at the Centennial Olympic Park scene where spectator Alice Hawthorne died. [25] Death and legacy [ edit] Jewell died on August 29, 2007, at the age of 44. He was suffering from serious medical problems that were related to diabetes. [4] Richard Jewell, a biographical drama film, was released in the United States on December 13, 2019. [26] The film was directed and produced by Clint Eastwood. It was written by Billy Ray, based on the 1997 article "American Nightmare: The Ballad of Richard Jewell, " by Marie Brenner, and the book The Suspect: An Olympic Bombing, the FBI, the Med"I hope and pray that no one else is ever subjected to the pain and the ordeal that I have gone through, " said Richard Jewell after the FBI publicly cleared him. "I am an innocent man. " Paul J. Richards/AFP/Getty Images Richard Jewell became the prime suspect of the Centennial Olympic Park bombing in which he was the first to discover the explosives before they detonated. In 1996, Richard Jewell became a hero after he successfully evacuated visitors before a bomb exploded in Atlanta’s Centennial Olympic Park. But after media reports surfaced that the FBI had made Jewell a prime suspect in the bombing, all hell broke loose, and the onetime hero turned into the villain. Media outlets across the country ? from the Atlanta Journal-Constitution to CNN ? painted Jewell as a pitiable wannabe cop desperate to play the hero, who would go so far as kill to cement his own enviable reputation. But, in reality, the FBI quickly stopped investigating him, and years later another man pled guilty to the crime. But it was all too late for Jewell, whose reputation was irrevocably tarnished. The infamous case was made into a feature film directed by Clint Eastwood with the eponymous title, Richard Jewell, as a reminder of how rushing to judgment can ruin lives. Who Was Richard Jewell? Doug Collier/AFP/Getty Images Richard Jewell (center), his mother (left), and his attorneys, Watson Bryant and Wayne Grant (far right), during a press conference after Jewell’s name was cleared. Before he jolted into the public consciousness, Richard Jewell led a fairly mundane life. He was born Richard White in Danville, Virginia, in 1962, and was raised in a strict Baptist home by his mother, Bobi. When he was four, his mother left his philandering father and soon married John Jewell, who adopted Richard as his own son. When Richard Jewell turned six, the family moved to Atlanta. As a boy, Jewell didn’t have many friends but the military-history buff kept busy on his own. “I was a wannabe athlete, but I wasn’t good enough, ” he told Vanity Fair in 1997. When he wasn’t reading books about the World Wars, he was either helping out teachers or taking volunteer jobs around school, like working as the school crossing guard or running the library’s projector. His dream was to be a car mechanic, and so after high school he enrolled in a technical school in southern Georgia. But three days into his new school, however, Bobi found out that Jewell’s stepfather had abandoned them. Jewell dropped out of his new school to be with his mother. After that, he worked all sorts of odd jobs, from managing a local yogurt shop to working as a jailer at the Habersham County Sheriff’s Office in northeastern Georgia. Doug Collier/AFP/Getty Images Richard Jewell attorney Lin Wood holds a copy of the Atlanta Journal-Constitution during a press conference. “She became overly protective of me. She looked at it that I was going to do the same thing that my dad did. I was 18 or 19. I was working, ” Jewell said of his mom. “She never liked my dates, but I never held that against her. We have always been able to lean on each other. ” Soon enough, he thought about going into law enforcement. In 1991, after a year working as a jailer, Jewel was promoted to deputy, and as part of his training he was sent to the Northeast Georgia Police Academy, where he finished in the top quarter of his class. From then on, it seemed Richard Jewell had found his calling. “To understand Richard Jewell, you have to be aware that he is a cop. He talks like a cop and thinks like a cop, ” said Jack Martin, Jewell’s attorney during the Olympic bombing investigation. Jewell’s commitment to upholding the letter of the law was obvious from his speech and the way he talked about things related to police work ? even after his mistreatment by the FBI. Paul J. Richards/AFP/Getty Images Richard Jewell’s primary attorney, Watson Bryant, assembled a team of lawyers to support Jewell during his high-profile investigation. Sometimes Jewell’s overzealousness led to unnecessary arrests. He was arrested for impersonating a police officer and was placed on probation on the condition that he seek psychological counseling. After wrecking his patrol car and being demoted back to jailer, Jewell quit the sheriff’s office and found another police job at Piedmont College, a tiny liberal arts school. Jewell’s heavy-handedness policing students caused tension with the school’s administrators. According to school officials, he was forced to resign from his post at Piedmont College. Jewell’s intense regard for law enforcement was later painted as an obsession, one that might motivate him to take extreme measures to achieve recognition. The 1996 Olympic Park Bombing Dimitri Iundt/Corbis/VCG/Getty Images One died and hundreds were seriously injured in the Centennial Olympic Park bombing. With the buzz around the 1996 Summer Olympics in Atlanta, just a 90-minute drive from Habersham County, Jewell figured there was a security job waiting for him there. It seemed like an opportune time since his mother, who still lived in Atlanta, was planning on undergoing foot surgery. He landed a position as one of the security guards working the 12-hour night shift. Little did he know that his new gig would soon throw his life into disarray. On July 26, 1996, according to Jewell, he left his mother’s house for the Olympic Park at 4:45 p. m. and arrived at the AT&T pavilion 45 minutes later. Photographers, television crews and reporters set up outside the apartment of Richard Jewell. His stomach was acting up so he took a break to go to the bathroom at around 10 p. Because of his terrible stomach cramps, Jewell used the closest bathroom, which was off-limits to staff, but the security guard gave him a pass. When he came back to his station near the sound-and-light tower by a music stage, Jewell noticed a group of drunks littering all over it. He later told an FBI agent that he remembered being annoyed at the group because they had caused a mess and were bothering camera crew. Being the vigilante he was, Jewell promptly went to report the drunken litter bugs. On his way, he spotted an olive-green military-style backpack that had been left unattended under the bench. At first, he didn’t think much of it, even joking about the contents of the bag with Tom Davis, an agent with the Georgia Bureau Of Investigation (GBI). “I was thinking to myself, ‘Well, I am sure one of these people left it on the ground, '” Jewell said. “When Davis came back and said, ‘Nobody said it was theirs, ’ that is when the little hairs on the back of my head began to stand up. I thought, ‘Uh-oh. This is not good. '” News of the FBI’s probe into Richard Jewell sparked a media frenzy. Both Jewell and Davis quickly cleared spectators out of a 25-square-foot area around the mystery backpack. Jewell also made two trips into the tower to evacuate the technicians. At about 1:25 a. on July 27, 1996, the backpack exploded, sending pieces of shrapnel onto the surrounding crowds. In the aftermath of the bomb, investigators found the perpetrator had planted nails inside a pipe bomb, a sinister creation meant to inflict maximum harm. Richard Jewell: Hero Or Perpetrator? Doug Collier/AFP/Getty Images Federal authorities searched the apartment for evidence that might link Jewell to the bombing. Not long after the explosion, Atlanta’s Centennial Olympic Park was swarming with federal agents. Richard Jewell, who spoke with the first agents to arrive at the scene, vividly remembered the chaotic scene following the bomb’s detonation, even a year later. “It was like what you hear in the movies. It was, like, kaboom, ” Jewell said, noting the dark morning sky turned a grayish-white because of the smoke. “I had seen an explosion in police training… All the shrapnel that was inside the package kept flying around, and some of the people got hit from the bench and some with metal. ” Later reports revealed a 911 call from a nearby phone booth had tipped dispatchers off to the threat: “There is a bomb in Centennial Park. You have 30 minutes. ” It had likely been the bomber. The Centennial Olympic Park explosion killed one woman and injured 111 others (a camera man also died of a heart attack while rushing to film the scene), but the casualties could’ve easily been much worse had the area not been partially evacuated. Once the press caught wind of Richard Jewell’s discovery of the bag and his preemptive efforts to steer the crowd to safety, he became a media fixture and was hailed as a hero. Doug Collier/AFP/Getty Images Officials prepare to tow the truck belonging to Richard Jewell, four days after a bomb exploded in Atlanta’s Centennial Olympic Park. But his fame turned to infamy after the Atlanta Journal-Constitution published a front-page story with the headline, “FBI Suspects ‘Hero’ Guard May Have Planted Bomb. ” Kathy Scruggs, a police reporter at the publication, had received a tip from a friend in the federal bureau that the agency was looking at Richard Jewell as a suspect in the bombing investigation. The tip was confirmed by another source who worked with the Atlanta police. Most damaging was one specific sentence in the piece: “Richard Jewell… fits the profile of the lone bomber, ” despite no public declarations by the FBI or criminal behavior experts. Other news outlets picked up the bombshell story and used similar language to profile Jewell, painting him as a loneman bomber and wannabe cop who wanted to be a hero. Doug Collier/AFP/Getty Images The media hounded Richard Jewell for 88 days until the U. S. Justice Department finally cleared his name from the investigation. “They were talking about an FBI profile of a hero bomber and I thought, ‘What FBI profile? ’ It rather surprised me, ” said the late Robert Ressler, a former FBI agent from the Behavioral Science Unit who interviewed notorious killers like Ted Bundy and Jeffre

This looks great. Movie Richard Jewell balladÃja ja. The movie should have ended with Richard Jewel doing the Macarena as the credits rolled. STARmeter SEE RANK Up 1, 481 this week View rank on IMDbPro ? On July 27, 1996, Richard Jewell was a security guard at the Summer Olympics in Atlanta, with aspirations of becoming a police officer. At around 1 a. m. in crowded Centennial Olympic Park, Jewell noticed an unattended green knapsack, alerted police and helped move people away from the site. The knapsack contained a crude pipe bomb, which exploded... See full bio ? Born: November 17, 1962 in Danville, Virginia, USA Died: August 29, 2007 (age 44) in Woodbury, Georgia, USA.

Atlanta Constitutional Journal Reporter, Kathy Scruggs was used and abused by the FBI to spread the story that Richard Jewell what is the suspect. The reason for this what is the FBI hoped that people would come out of the woodwork with information about Jewell once he was identified as a suspect, that would somehow help them make their case. Scruggs was a young woman that knew how to have fun, display her sex appeal, drink, smoke and abuse drugs. Scruggs got her drugs from Atlanta Cops and slept with several of them which is no big deal until she died of a drug overdose at 41. She got a lot of her news tips during pillow talk. The fact is she got good information most of the time and wrote good news stories.

The MSM is a double edged sword. And people wonder why no one trusts the MSM. It was rikishi he did for the rock. Looks like you are using an unsupported browser. To get the most out of this experience please upgrade to the latest version of Internet Explorer.

Great movie! Highly underrated.

Great movie! Highly underrated.Responsible reporting? I haven't seen that since the 80's. Philip Seymour Hoffman was BORN to play this... ?. A film is nice, but someone should make a documentary. Movie Richard Jewell balladÃja rule.

Damn. I didnt know CNN did fake news that long ago. Movie Richard Jewell balladÃjardin. Movie Richard Jewell balladÃja 日本. Movie Richard Jewell balladÃ. Blondie has the absolute power to bring forth the best from us. Movie Richard Jewell balladÃpedia.

Movie Richard Jewell balladÃja.d.e. Credit... Greg Gibson/Associated Press, 1997 ATLANTA, Aug. 29 ? Richard A. Jewell, whose transformation from heroic security guard to Olympic bombing suspect and back again came to symbolize the excesses of law enforcement and the news media, died Wednesday at his home in Woodbury, Ga. He was 44. The cause of death was not released, pending the results of an autopsy that will be performed Thursday by the Georgia Bureau of Investigation. But the coroner in Meriwether County, about 60 miles southwest of here, said that Mr. Jewell died of natural causes and that he had battled serious medical problems since learning he had diabetes in February. The coroner, Johnny E. Worley, said that Mr. Jewell’s wife, Dana, came home from work Wednesday morning to check on him after not being able to reach him by telephone. She found him dead on the floor of their bedroom, he said. Mr. Worley said Mr. Jewell had suffered kidney failure and had had several toes amputated since the diabetes diagnosis. “He just started going downhill ever since, ” Mr. Worley said. The heavy-set Mr. Jewell, with a country drawl and a deferential manner, became an instant celebrity after a bomb exploded in Centennial Olympic Park in Atlanta in the early hours of July 27, 1996, at the midpoint of the Summer Games. The explosion, which propelled hundreds of nails through the darkness, killed one woman, injured 111 people and changed the mood of the Olympiad. Only minutes earlier, Mr. Jewell, who was working a temporary job as a guard, had spotted the abandoned green knapsack that contained the bomb, called it to the attention of the police, and started moving visitors away from the area. He was praised for the quick thinking that presumably saved lives. But three days later, he found himself identified in an article in The Atlanta Journal as the focus of police attention, leading to several searches of his apartment and surveillance by the Federal Bureau of Investigation and by reporters who set upon him, he would later say, “like piranha on a bleeding cow. ” The investigation by local, state and federal law enforcement officers lasted until late October 1996 and included a number of bungled tactics, including an F. B. I. agent’s effort to question Mr. Jewell on camera under the pretense of making a training film. In October 1996, when it became obvious that Mr. Jewell had not been involved in the bombing, the Justice Department formally cleared him. “The tragedy was that his sense of duty and diligence made him a suspect, ” said John R. Martin, one of Mr. Jewell’s lawyers. “He really prided himself on being a professional police officer, and the irony is that he became the poster child for the wrongly accused. ” In 2005, Eric R. Rudolph, a North Carolina man who became a suspect in the subsequent bombing of an abortion clinic in Birmingham, Ala., pleaded guilty to the Olympic park attack. He is serving a life sentence. Even after being cleared, Mr. Jewell said he never felt he could outrun his notoriety. He sued several major news media outlets and won settlements from NBC and CNN. His libel case against his primary nemesis, Cox Enterprises, the Atlanta newspaper’s parent company, wound through the courts for a decade without resolution, though much of it was dismissed along the way. After memories of the case subsided, Mr. Jewell took jobs with several small Georgia law enforcement agencies, most recently as a Meriwether County sheriff’s deputy in 2005. Col. Chuck Smith, the chief deputy, called Mr. Jewell “very, very conscientious” and said he also served as a training officer and firearms instructor. Jewell is survived by his wife and by his mother, Barbara. Last year, Mr. Jewell received a commendation from Gov. Sonny Perdue, who publicly thanked him on behalf of the state for saving lives at the Olympics.

Movie Richard Jewell balladÃja 日. Sorry, but If I see a hazard, I'm leaving the scene and not reporting anything. I'm not going through this. They havent learned anything. Who's here after the trailer.

Movie Richard Jewell balladÃja 日. Sorry, but If I see a hazard, I'm leaving the scene and not reporting anything. I'm not going through this. They havent learned anything. Who's here after the trailer.  The most recent film directed by Clint Eastwood, again based on a true story, surprises first with the narrative skill that the man has a director at 89 years old. He is a very skilled narrator whose films are usually entertaining, engaging and emotional. It also stands out for the great staging that involves the recreation of a stage in which the 1996 Atlanta Olympics were held; the crowd scenes, the newspaper office, Richard's mom's apartment. Everything is well set and credible. I also highlight all the performances, each character is well delineated.

The most recent film directed by Clint Eastwood, again based on a true story, surprises first with the narrative skill that the man has a director at 89 years old. He is a very skilled narrator whose films are usually entertaining, engaging and emotional. It also stands out for the great staging that involves the recreation of a stage in which the 1996 Atlanta Olympics were held; the crowd scenes, the newspaper office, Richard's mom's apartment. Everything is well set and credible. I also highlight all the performances, each character is well delineated.The problem for me is that the conclusion of the story occurs prematurely and I feel that the arches of the secondary characters do not close: the FBI agent, the reporter and the lawyer. That subtracted emotion from the impact of the story. I also felt that the film takes a while to start with its main conflict. It could have spent less time at the beginning and more at the end. However, it is a product worth checking out at this beginning of the year.This will be in theaters about the time the next FBI scandal is blowing wide open. Séances Bandes-annonces Casting Critiques spectateurs Critiques presse Photos VOD noter: 0. 5 1 1. 5 2 2. 5 3 3. 5 4 4. 5 5 Envie de voir Rédiger ma critique Synopsis et détails En 1996, Richard Jewell fait partie de l'équipe chargée de la sécurité des Jeux d'Atlanta. Il?est l'un des premiers à alerter de la présence d'une bombe et à sauver des vies. Mais il se retrouve bientôt suspecté... de terrorisme,?passant du statut de héros à celui d'homme le plus détesté des Etats-Unis. Il fut innocenté trois mois plus tard par le FBI mais sa réputation ne fut jamais complètement rétablie, sa santé étant endommagée par l'expérience. Titre original Richard Jewell Distributeur Warner Bros. France Récompenses 2 nominations Voir les infos techniques 2:20 Acteurs et actrices Casting complet et équipe technique 27 Photos Secrets de tournage Histoire vraie Le 27 juillet 1996, pendant les Jeux Olympiques d’été à Atlanta, un vigile du nom de Richard Jewell découvre un sac à dos suspect caché derrière un banc. Très vite, on se rend compte qu’il contient un dispositif explosif. Sans perdre une minute, il fait évacuer les lieux et sauve plusieurs vies en limitant le nombre de blessés. Il est acclamé en héros. Mais trois jours plus tard, la vie de ce modeste sauveteur bascule lorsqu’il découvre, en même... Lire plus Paul Greengrass et DiCaprio au casting? Le projet avait été annoncé avec la présence de Leonardo DiCaprio?au casting au côtés de Jonah Hill pour jouer l'avocat de Jewell. Le film devait alors être réalisé par Paul Greengrass. Pourquoi un biopic? Très touché par ce héros ordinaire, Richard Jewell,?Clint Eastwood a souhaité porter à l'écran l’histoire tragique de cet homme bienveillant, dont la vie a été bouleversée par la presse et par les forces de police qu’il idolâtrait. "On entend souvent parler de gens puissants qui se font accuser de choses et d’autres, mais ils ont de l’argent, ils font appel à un bon avocat et échappent aux poursuite. L’histoire de Richard Jewell m’a intéress... 17 Secrets de tournage Dernières news 10 news sur ce film Si vous aimez ce film, vous pourriez aimer... Voir plus de films similaires Commentaires.

This man was railroaded. He did his job, and saved hundreds of people. May he rest in peace and be remembered as a hero.

- Coauthor: The UnCola

- Resume: We play forgotten pop from the last 50 years every Tuesday night from 8-10pm live on 103.3 Asheville FM - Since 2009.

コメントをかく