批判サイド>否定論・陰謀論を信じる理由 > 科学への抵抗感

大人にみられる"科学への抵抗感"の要因についてのレビュー論文をとりあげる。

このBloom and Weisberg[2007]は、物理世界への直感的理解と心理学的直観という常識に、科学が反していることを要因のひとつに挙げている。

まず、物理世界への直観的理解の例として、直観的"慣性の法則"を挙げている:

直観的"慣性の法則"では、曲線運動がそのまま続ようだ。そして、その直観は実体験で、あっさり消されるという。

続いて、これまでも取り上げてきた、意図や目的を読み取ってしまう心理学的直観:

ここで言われている目的論選好がただちに創造論につながるかは議論の余地があるだろう。たとえば、アセンション系スピリチュアルな"進化"も、創造論と同じく目的・意図・デザインを自然現象の背後に見出している。もちろん、スピリチュアルな"進化"は、通常科学の進化とは別物で、反進化論のカテゴライズされるべきものだが。

で、さらにBloom and Weisberg[2007]は、「脳と心の二元論」という「心理学的直観」を挙げる:

"非物質的魂"によって人間とそれ以外を分かつのはキリスト教系の教義であって、仏教系だと人間とそれ以外の動物を厳格に分かつ教義にはなっていない。その点で、「胚や胎児や肝細胞と人間以外の動物の倫理的ステータス」に魂を持ち出すのは文化依存性かもしれない。

しかし、「私の脳が私をそうさせた」という言い訳のようなものは、キリスト教系の教義とのつながりは見いだせない。明示的な「脳と心の二元論」は文化依存だったとしても、暗黙に「脳と心」を分かつような思考は、脳の実装かもしれない。

これらの研究によれば、情報ソースが提示されない形で語られるもの、存在が前提となっているものについて、人間は疑問を持たないようだ。疑問を持つようでは、言語も習得不可能になるかもしれない。

一方、批判的思考をバイパスしない場合とは...

批判的思考を通過するといっても、情報それ自体の正否を確認できずに、情報ソースの信頼性に依存して判断することになるようだ。確かに数学が科学の不可欠な構成要素なったことで、科学は素人に手の出せるものではなくなっている。気象・気候はもちろんのこと、生態学や動物行動学といえども1970年代には数理化された。

ただ、ひとり数学だけが理解・評価の障害となるわけではないようだ。情報そのものではなく、情報ソースを評価対象にしてしまうのは、"支持する政策"にも見られるという

そして、「物理世界についての直観と心理学的直観」に反した科学への抵抗が、「情報それ自体の正否を確認できずに、情報ソースの信頼性に依存して判断する」ことにより、信頼する宗教および政治的権威によって強化されることが、米国における創造論支持の多さの要因ではないかと、 Bloom and Weisberg[2007]は結論する:

大人にみられる"科学への抵抗感"の要因についてのレビュー論文をとりあげる。

このBloom and Weisberg[2007]は、物理世界への直感的理解と心理学的直観という常識に、科学が反していることを要因のひとつに挙げている。

まず、物理世界への直観的理解の例として、直観的"慣性の法則"を挙げている:

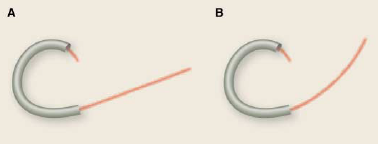

foundational biases persist into adulthood. One study tested college undergraduates’ intuitions about basic physical motions, such as the path that a ball will take when released from a curved tube (13). Many of the undergraduates retained a common-sense Aristotelian theory of object motion; they predicted that the ball would continue to move in a curved motion, choosing B over A in Fig. 1. An interesting addendum is that although education does not shake this bias, real-world experience can suffice. In another study, undergraduates were asked about the path that water would take out of a curved hose. This corresponded to an event that the participants had seen, and few believed that the water would take a curved path (14).

根本的なバイアスが大人になっても残る。大学の学生を使った研究では、曲った管から射出されるボールの動きの予測のような、基本的な物理運動について質問した[13]。多くの学生たちは常識的なアリストテレスの物体運動論を持っていた。学生たちは、Fig1のAではなくBすなわち、曲った運動を続ける方を選択した。面白いことに、教育では、このバイアスをどうにもできないが、実世界の体験では十分にバイアスを消せる。他の研究では、学生たちは曲ったホースから出る水の動きを質問された。これはテスト参加者が見たことがある情景であり、水が曲がって出ると信じていた学生はほとんどいなかった[14]。

[13] M. McCloskey, A. Caramazza, B. Green, Science 210, 1139 (1980).

[14] M. K. Kaiser, J. Jonides, J. Alexander, Mem. Cogn. 14, 308 (1986).

直観的"慣性の法則"では、曲線運動がそのまま続ようだ。そして、その直観は実体験で、あっさり消されるという。

続いて、これまでも取り上げてきた、意図や目的を読み取ってしまう心理学的直観:

The examples so far concern people’s common-sense understanding of the physical world, but their intuitive psychology also contributes to their resistance to science. One important bias is that children naturally see the world in terms of design and purpose. For instance, 4-year-olds insist that everything has a purpose, including lions (“to go in the zoo”) and clouds (“for raining”), a propensity called “promiscuous teleology” (15). Additionally, when asked about the origin of animals and people, children spontaneously tend to provide and prefer creationist explanations (16). Just as children’s intuitions about the physical world make it difficult for them to accept that Earth is a sphere, their psychological intuitions about agency and design make it difficult for them to accept the processes of evolution.

先の例は、人々が持っている物理世界の常識的理解による問題だった。しかし、彼らの直観的な真理もまた、科学への抵抗に関与する。ひとつの重要なバイアスは、子供たちが自然に世界をデザインと目的の言葉で見ることである。たとえば、4歳児はあらゆるもに目的があると主張する。たとえば、「動物園に行くためのライオン」とか「雨を降らすための雲」など、その傾向は「無差別な目的論」と呼ばれる[15]。さらに、動物と人間の起源について問うと、子供たちは創造論者の説明を自発的に提示し、選好する傾向を示す[16]。子供たちの物理世界に対する直観が、地球が丸いことを受け入れ難くするように、子供たちのエージェンシーとデザインについての心理学的直観は、進化の過程を受け入れ難くする。

[15] D. Kelemen, Cognition 70, 241 (1999).

[16] M. Evans, Cognit. Psychol. 42, 217 (2001).

ここで言われている目的論選好がただちに創造論につながるかは議論の余地があるだろう。たとえば、アセンション系スピリチュアルな"進化"も、創造論と同じく目的・意図・デザインを自然現象の背後に見出している。もちろん、スピリチュアルな"進化"は、通常科学の進化とは別物で、反進化論のカテゴライズされるべきものだが。

で、さらにBloom and Weisberg[2007]は、「脳と心の二元論」という「心理学的直観」を挙げる:

Another consequence of people’s commonsense psychology is dualism, the belief that the mind is fundamentally different from the brain (5). This belief comes naturally to children. Preschool children will claim that the brain is responsible for some aspects of mental life, typically those involving deliberative mental work, such as solving math problems. But preschoolers will also claim that the brain is not involved in a host of other activities, such as pretending to be a kangaroo, loving one’s brother, or brushing one’s teeth (5, 17). Similarly, when told about a brain transplant from a boy to a pig, they believed that you would get a very smart pig, but one with pig beliefs and pig desires (18). For young children, then, much of mental life is not linked to the brain.

人々の常識的心理学の帰結は、二元論、すなわち心と脳が根本的に異なるという信念である[5]。この信念は子供たちにとっては自然である。学齢未満の子供たちは、数学の問題を解くような精神的作業に関するものなど、精神生活のある面について脳によるものだと主張する。しかし、カンガルーのふりをするとか、兄弟を愛するとか、歯を磨くといった別の精神活動は脳によるものではないと主張する[5,17]。同様に、脳が少年からブタに移植されたどうなるか問うと、子供たちはブタは賢くなると信じるが、信条や欲望はブタのものになると応える[18]。子供たちにとって、精神生活の多くの面は脳とリンクしていない。

The strong intuitive pull of dualism makes it difficult for people to accept what Francis Crick called “the astonishing hypothesis” (19): Dualism is mistaken -- mental life emerges from physical processes. People resist the astonishing hypothesis in ways that can have considerable social implications. For one thing, debates about the moral status of embryos, fetuses, stem cells, and nonhuman animals are sometimes framed in terms of whether or not these entities possess immaterial souls (20, 21). What’s more, certain proposals about the role of evidence from functional magnetic resonance imaging in criminal trials assume a strong form of dualism (22). It has been argued, for instance, that if one could show that a person’s brain is involved in an act, then the person himself or herself is not responsible, an excuse dubbed “my brain made me do it” (23). These assumptions about moral status and personal responsibility reflect a profound resistance to findings from psychology and neuroscience.

二元論の強い直観力は、人々にFrancis Crickが"the astonishing hypothesis"と呼ぶ仮説「二元論は誤りであり、精神生活は物理過程によって生じる」を受け入れ難くする。人々は、そレが持つ社会的意味に絡んで、"the astonishing hypothesis"に抵抗する。たとえば、胚や胎児や肝細胞と人間以外の動物の倫理的ステータスについて議論するとき、ときとして、これらの存在が非物質的魂を持っているか否かというフレーミングがさなれることがある[20,21]。裁判において、fMRIによって得られた証拠の役割について、強い意味での二元論を仮定した提案がなされることがある[22]。たとえば、脳が行為を起こさせたのであれば、その人物には責任はなく、「私の脳が私をそうさせた」という言い訳を主張する[23]。倫理ステータスと個人の責任に関する、これらの仮定は心理学と神経科学発見に対する深い抵抗を反映している。

[ 5] P. Bloom, Descartes’ Baby (Basic Books, New York, 2004).

[17] A. S. Lillard, Child Dev. 67, 1717 (1996).

[18] C. N. Johnson, Child Dev. 61, 962 (1990).

[19] F. Crick, The Astonishing Hypothesis (Simon & Schuster, New York, 1995).

[20] This belief in souls also holds for some expert ethicists. For instance, in their 2003 report Being Human: Readings from the President's Council on Bioethics, the President’s Council described people as follows: “We have both corporeal and noncorporeal aspects. We are embodied spirits and inspirited bodies (or, if you will, embodied minds and minded bodies)” (21).

[21] The President’s Council on Bioethics, Being Human: Readings from the President's Council on Bioethics (The President’s Council on Bioethics, Washington, DC, 2003).

[22] J. D. Greene, J. D. Cohen, Philos. Trans. R. Soc. London Ser. B 359, 1775 (2004).

[23] M. Gazzaniga, The Ethical Brain (Dana, Chicago, 2005).

"非物質的魂"によって人間とそれ以外を分かつのはキリスト教系の教義であって、仏教系だと人間とそれ以外の動物を厳格に分かつ教義にはなっていない。その点で、「胚や胎児や肝細胞と人間以外の動物の倫理的ステータス」に魂を持ち出すのは文化依存性かもしれない。

しかし、「私の脳が私をそうさせた」という言い訳のようなものは、キリスト教系の教義とのつながりは見いだせない。明示的な「脳と心の二元論」は文化依存だったとしても、暗黙に「脳と心」を分かつような思考は、脳の実装かもしれない。

The main reason why people resist certain scientific findings, then, is that many of these findings are unnatural and unintuitive. But this does not explain cultural differences in resistance to science. There are substantial differences, for example, in how quickly children from different countries come to learn that Earth is a sphere (10). There is also variation across countries in the extent of adult resistance to science, including the finding that Americans are more resistant to evolutionary theory than are citizens of most other countries (24).

人々が特定の科学的発見に抵抗する主たる理由は、これらの発見の多くが不自然であり、直観的ではないことである。しかし、これは科学への抵抗についての文化的違いを説明するものではない。たとえば、異なる国々の子供たちが地球が丸いことを学ぶ速さに、大きな違いがある[10]。また、米国人が進化論に対する抵抗が他の国々よりも大きいといった、科学に対する大人たちの抵抗にも国ごとの違いがある[24]。

Part of the explanation for such cultural differences lies in how children and adults process different types of information. Some culture specific information is not associated with any particular source; it is “common knowledge.” As such, learning of this type of information generally bypasses critical analysis. A prototypical example is that of word meanings. Everyone uses the word “dog” to refer to dogs, so children easily learn that this is what they are called (25). Other examples include belief in germs and electricity. Their existence is generally assumed in day-to-day conversation and is not marked as uncertain; nobody says that they “believe in electricity.” Hence, even children and adults with little scientific background believe that these invisible entities really exist (26).

そのような文化による違いの説明のひとつが、子供たちと大人たちが異なるタイプの情報に対処する方法にある。ある文化に特有な情報は特定の情報ソースに関連していない。それは常識である。そのような情報の学習は、一般に批判的分析をバイパスする。典型的な例は言葉の意味である。「イヌ」という言葉を誰もがイヌに対して使っているので、子供たちは容易に、これが誰もがイヌと呼ぶものであることを学習できる[25]。同様の例は、細菌と電気である。日々の会話において、最近や電気の存在は前提とされており、不確かなものとは見られていない。だれも「電気を信じる」とは言わない。したがって、子供たちや、科学的知識があまりない大人たちも、細菌や電気という見えないものが本当に存在していると信じる[26]。

[10] M. Siegal, G. Butterworth, P. A. Newcombe, Dev. Sci. 7, 308 (2004).

[24] J. D. Miller, E. C. Scott, S. Okamoto, Science 313, 765 (2006).

[25] P. Bloom, How Children Learn the Meanings of Words (MIT Press, Cambridge, MA, 2000).

[26] P. L. Harris, E. S. Pasquini, S. Duke, J. J. Asscher, F. Pons, Dev. Sci. 9, 76 (2006).

これらの研究によれば、情報ソースが提示されない形で語られるもの、存在が前提となっているものについて、人間は疑問を持たないようだ。疑問を持つようでは、言語も習得不可能になるかもしれない。

一方、批判的思考をバイパスしない場合とは...

Other information, however, is explicitly asserted, not tacitly assumed. Such asserted information is associated with certain sources. A child might note that science teachers make surprising claims about the origin of human beings, for instance, whereas their parents do not. Furthermore, the tentative status of this information is sometimes explicitly marked; people will assert that they “believe in evolution.”

しかし、別な情報は、暗黙の仮定ではなく、直接に断言される。このような断言された情報には特定の情報ソースがついている。両親が決してしないが、理科の先生が人間の起源について行う主張に、子供たちは注意を払うかもしれない。さらに、この情報の一時的ステータスは時として明示的に示される。人々は「進化論を信じる」と言う。

When faced with this kind of asserted information, one can occasionally evaluate its truth directly. But in some domains, including much of science, direct evaluation is difficult or impossible. Few of us are qualified to assess claims about the merits of string theory, the role of mercury in the etiology of autism, or the existence of repressed memories. So rather than evaluating the asserted claim itself, we instead evaluate the claim’s source. If the source is deemed trustworthy, people will believe the claim, often without really understanding it. Consider, for example, that many Americans who claim to believe in natural selection are unable to accurately describe how natural selection works (3). This suggests that their belief is not necessarily rooted in an appreciation of the evidence and arguments. Rather, this scientifically credulous subpopulation accepts this information because they trust the people who say it is true.

この種の断言された情報に接したとき、人はときおり、それが正しいか直接に評価できる。しかし、多くの科学を含む、ある種の分野では、直接の評価が困難であるか、不可能である。我々の大半は超弦理論のメリットや、自閉症の病因論における水銀の役割や、抑圧された記憶の存在についての主張を、評価できない。したがって、我々は、断言された主張を評価するのではなく、代りに、主張の情報ソースを評価する。情報ソースが信頼に値するなら、実際に理解することなく、その主張を信じる。たとえば、自然選択を信じると主張する多くの米国人は、自然選択の働きを正しく記述できない[3]。これは、人々が信じるのは、必ずしも証拠と議論によるものではないことを示唆している。むしろ、これらの科学を信じる人々は、それが正しいと言っている人々を信頼して、これらの情報を受け入れているのである。

[ 3] Andrew Shtulman: "Qualitative diVerences between naïve and scientific theories of evolution", Cognitive Psychology 52, 170-194, 2006

批判的思考を通過するといっても、情報それ自体の正否を確認できずに、情報ソースの信頼性に依存して判断することになるようだ。確かに数学が科学の不可欠な構成要素なったことで、科学は素人に手の出せるものではなくなっている。気象・気候はもちろんのこと、生態学や動物行動学といえども1970年代には数理化された。

ただ、ひとり数学だけが理解・評価の障害となるわけではないようだ。情報そのものではなく、情報ソースを評価対象にしてしまうのは、"支持する政策"にも見られるという

Science is not special here; the same process of deference holds for certain religious, moral, and political beliefs as well. In an illustrative recent study, participants were asked their opinion about a social welfare policy that was described as being endorsed by either Democrats or Republicans. Although the participants sincerely believed that their responses were based on the objective merits of the policy, the major determinant of what they thought of the policy was, in fact, whether or not their favored political party was said to endorse it (27). Additionally, many of the specific moral intuitions held by members of a society appear to be the consequence, not of personal moral contemplation, but of deference to the views of the community (28).

科学だけが特別なのではない。同じ従属のプロセスが、宗教や倫理や政治の信条にある。実証的な最近の研究では、被験者たちは、民主党もしくは共和党が推奨するものとして書かれた社会福祉政策について意見を求められた。被験者たちは、政策の客観的なメリットに基づいて意見を述べたと本当に信じていたが、実際には、政策についての意見の決定要因は、その政策を推奨した政党を支持しているか否かだった[27]。さらに、ある社会の構成員が持つ特定の倫理的直観の多くは、個人的な倫理的考慮の結果ではなく、コミュニティの見方への従属の結果である[28]。

[27] G. L. Cohen, J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 85, 808 (2003).

[28] J. Haidt, Psychol. Rev. 108, 814 (2001).

そして、「物理世界についての直観と心理学的直観」に反した科学への抵抗が、「情報それ自体の正否を確認できずに、情報ソースの信頼性に依存して判断する」ことにより、信頼する宗教および政治的権威によって強化されることが、米国における創造論支持の多さの要因ではないかと、 Bloom and Weisberg[2007]は結論する:

These developmental data suggest that resistance to science will arise in children when scientific claims clash with early emerging, intuitive expectations. This resistance will persist through adulthood if the scientific claims are contested within a society, and it will be especially strong if there is a nonscientific alternative that is rooted in common sense and championed by people who are thought of as reliable and trustworthy. This is the current situation in the United States, with regard to the central tenets of neuroscience and evolutionary biology. These concepts clash with intuitive beliefs about the immaterial nature of the soul and the purposeful design of humans and other animals, and (in the United States) these beliefs are particularly likely to be endorsed and transmitted by trusted religious and political authorities (24). Hence, these fields are among the domains where Americans’ resistance to science is the strongest.

これらの発育上のデータは、科学的主張と子供の頃に出現する直観から期待されるものと衝突することによって、科学への抵抗感が生じることを示唆している。この科学への抵抗感は、科学的主張について社会的に争いがあると、大人になっても失われない。特に常識や信頼できる人々の主張に根ざす非科学的代替論があると、この抵抗感は強くなる。これが、神経科学や進化生物学の中心的見解についての、米国の現状である。これら神経科学や進化生物学の概念は、魂の非物質性や人間や動物の意図的デザインに関する直観的信条と衝突しており、米国において、これらの信条は特に、信頼できる宗教および政治的権威によって推奨される[24]。従って、これらが、米国人の科学への抵抗感が最も強い分野となっている。

[24] J. D. Miller, E. C. Scott, S. Okamoto, Science 313, 765 (2006).

コメントをかく