*

????????????

https://rqzamovies.com/m16728.html

????????????

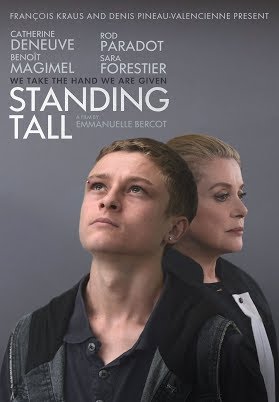

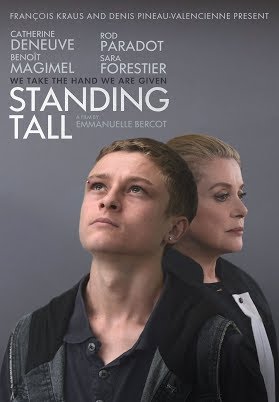

&ref(https://m.media-amazon.com/images/M/MV5BMGIyYTI1NTQtODlhYS00NzczLTg1MTgtMWNjZDYyZjUyZjlkXkEyXkFqcGdeQXVyNjM2OTI5Mzg@._V1_UX182_CR0,0,182,268_AL_.jpg) / Directed by - Neil Goss / reviews - Broken teens trying to claim somethings their parents failed to provide - A Future and Purpose / Actor - Demitra Sealy. Shop for Books on Google Play Browse the world's largest eBookstore and start reading today on the web, tablet, phone, or ereader. Go to Google Play Now ?.

Suggested Citation: "The Juvenile Justice System. " National Research Council and Institute of Medicine. 2001. Juvenile Crime, Juvenile Justice. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. doi: 10. 17226/9747. × 5 The Juvenile Justice System A separate juvenile justice system was established in the United States about 100 years ago with the goal of diverting youthful offenders from the destructive punishments of criminal courts and encouraging rehabilitation based on the individual juvenile's needs. This system was to differ from adult or criminal court in a number of ways. It was to focus on the child or adolescent as a person in need of assistance, not on the act that brought him or her before the court. The proceedings were informal, with much discretion left to the juvenile court judge. Because the judge was to act in the best interests of the child, procedural safeguards available to adults, such as the right to an attorney, the right to know the charges brought against one, the right to trial by jury, and the right to confront one's accuser, were thought unnecessary. Juvenile court proceedings were closed to the public and juvenile records were to remain confidential so as not to interfere with the child's or adolescent's ability to be rehabilitated and reintegrated into society. The very language used in juvenile court underscored these differences. Juveniles are not charged with crimes, but rather with delinquencies; they are not found guilty, but rather are adjudicated delinquent; they are not sent to prison, but to training school or reformatory. In practice, there was always a tension between social welfare and social control?that is, focusing on the best interests of the individual child versus focusing on punishment, incapacitation, and protecting society from certain offenses. This tension has shifted over time and has varied significantly from jurisdiction to jurisdiction, and it remains today. In response to the increase in violent crime in the 1980s, state legal reforms in juvenile justice, particularly those that deal with serious offenses, have stressed punitiveness, accountability, and a concern for public safety, rejecting traditional concerns for diversion and rehabilitation in favor of a get-tough approach to juvenile crime and punishment. This change in emphasis from a focus on rehabilitating the individual to punishing the act is exemplified by the 17 states that redefined the purpose clause of their juvenile courts to emphasize public safety, certainty of sanctions, and offender accountability (Torbet and Szymanski, 1998). Inherent in this change in focus is the belief that the juvenile justice system is too soft on delinquents, who are thought to be potentially as much a threat to public safety as their adult criminal counterparts. It is important to remember that the United States has at least 51 different juvenile justice systems, not one. Each state and the District of Columbia has its own laws that govern its juvenile justice system. How juvenile courts operate may vary from county to county and municipality to municipality within a state. The federal government has jurisdiction over a small number of juveniles, such as those who commit crimes on Indian reservations or in national parks, and it has its own laws to govern juveniles within its system. States that receive money under the federal Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention Act must meet certain requirements, such as not housing juveniles with adults in detention or incarceration facilities, but it is state law that governs the structure of juvenile courts and juvenile corrections facilities. When this report refers to the juvenile justice system, it is referring to a generic framework that is more or less representative of what happens in any given state. Legal reforms and policy changes that have taken place under the get-tough rubric include more aggressive policing of juveniles, making it easier (or in some cases mandatory) to treat a juvenile who has committed certain offenses as an adult, moving decision making about where to try a juvenile from the judge to the prosecutor or the state legislature, changing sentencing options, and opening juvenile proceedings and records. Changes in laws do not necessarily translate into changes in practice. In addition to the belief that at least some juvenile offenders are amenable to treatment and rehabilitation, other factors limit overreliance on get-tough measures: (1) the expense of incarceration, (2) overcrowding that results from sentencing offenders more harshly, and (3) research evidence that finds few gains, in terms of reduced rates of recidivism, from simply incapacitating youth without any attention to treatment or rehabilitation (Beck and Shipley, 1987; Byrne and Kelly, 1989; Hagan, 1991; National Research Council, 1993a; National Research Council, 1993b; Shannon et al., 1988). Practice may also move in ways not envisioned when laws are passed. For example, many jurisdictions have been experimenting with alternative models of juvenile justice, such as the restorative justice model. Whereas the traditional juvenile justice model focuses attention on offender rehabilitation and the current get-tough changes focus on offense punishment, the restorative model focuses on balancing the needs of victims, offenders, and communities (Bazemore and Umbreit, 1995). Tracking changes in practice is difficult, not only because of the differences in structure of the juvenile justice system among the states, but also because the information collected about case processing and about incarcerated juveniles differs from state to state, and because there are few national data. Some states collect and publish a large amount of data on various aspects of the juvenile justice system, but for most states the data are not readily available. Although data are collected nationally on juvenile court case processing, 1 the courts are not required to submit data, so that national juvenile court statistics are derived from courts that cover only about two-thirds of the entire juvenile population (Stahl et al., 1999). Furthermore, there are no published national data on the number of juveniles convicted by offense, the number incarcerated by offense, sentence length, time served in confinement, or time served on parole (Langan and Farrington, 1998). 2 Such national information is available on adults incarcerated in prisons and jails. The center of the juvenile justice system is the juvenile or family court (Moore and Wakeling, 1997). In fact, the term juvenile justice is often used synonymously with the juvenile court, but it also may refer to other affiliated institutions in addition to the court, including the police, prosecuting and defense attorneys, probation, juvenile detention centers, and juvenile correctional facilities (Rosenheim, 1983). In this chapter, juvenile justice is used in the latter, larger sense. After providing a brief historical background of the juvenile court and a description of stages in the juvenile justice system, we examine the various legal and policy changes that have taken place in recent years, the impact those changes have had on practice, and the result of the laws, policy, and practice on juveniles caught up in the juvenile justice system. Throughout the chapter, differences by race and by gender in involvement in the juvenile justice system are noted. Chapter 6 examines in more detail the overrepresentation of minorities in the juvenile justice system. 1 The National Center for Juvenile Justice, under contract with the Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention, U. S. Department of Justice, has collected and analyzed juvenile court statistics since 1975. 2 Data on the first two categories are already collected but not published. Data on the latter three categories are not now collected nationally. HISTORY OF THE JUVENILE JUSTICE SYSTEM Until the early 19th century in the United States, children as young as 7 years old could be tried in criminal court and, if convicted, sentenced to prison or even to death. Children under the age of 7 were presumed to be unable to form criminal intent and were therefore exempt from punishment. The establishment of special courts and incarceration facilities for juveniles was part of Progressive Era reforms, along with kindergarten, child labor laws, mandatory education, school lunches, and vocational education, that were aimed at enhancing optimal child development in the industrial city (Schlossman, 1983). Reformers believed that treating children and adolescents as adult criminals was unnecessarily harsh and resulted in their corruption. In the words of one reformer, the main reason for the establishment of the juvenile court was “to prevent children from being treated as criminals ” (Van Waters, 1927:217). Based on the premise that children and young adolescents are developmentally different from adults and are therefore more amenable to rehabilitation, and that they are not criminally responsible for their actions, children and adolescents brought before the court were assumed to require the court's intervention and guidance, rather than solely punishment. They were not to be accused of specific crimes. The reason a juvenile came before the court?be it for committing an offense or because of abuse or neglect by his or her parents or for being uncontrollable?was less important than understanding the child's life situation and finding appropriate, individualized rehabilitative services (Coalition for Juvenile Justice, 1998; Schlossman, 1983). Historians have noted that the establishment of the juvenile court not only diverted youngsters from the criminal court, but also expanded the net of social control over juveniles through the incorporation of status jurisdiction into states' juvenile codes (e. g., Platt, 1977; Schlossman, 1977). The first juvenile court in the United States, authorized by the Illinois

Watch Full Length Juvenile delinquent. Criminology and penology Theory Anomie Biosocial criminology Broken windows Collective efficacy Crime analysis Criminalization Differential association Deviance Labeling theory Psychopathy Rational choice Social control Social disorganization Social learning Strain Subculture Symbolic interactionism Victimology Types of crime Against humanity Blue-collar Corporate Juvenile Organized Political Public-order State State-corporate Victimless White-collar War Methods Comparative Profiling Critical theory Ethnography Uniform Crime Reports Crime mapping Positivist school Qualitative Quantitative BJS NIBRS Penology Denunciation Deterrence Incapacitation Trial Prison abolition open reform Prisoner Prisoner abuse Prisoners' rights Rehabilitation Recidivism Justice in penology Participatory Restorative Retributive Solitary confinement Schools Anarchist criminology Chicago school Classical school Conflict criminology Critical criminology Environmental criminology Feminist school Integrative criminology Italian school Left realism Marxist criminology Neo-classical school Postmodernist school Right realism Subfields American Anthropological Conflict Criminology Critical Culture Cyber Demography Development Environmental Experimental Organizational Public Radical criminology Browse Index Journals Organizations People v t e Part of the Politics series on Youth rights Activities Bailey v. Drexel Furniture Co. Child Labor Deterrence Act Children's Online Privacy Protection Act Convention on the Rights of the Child Fair Labor Standards Act Hammer v. Dagenhart History of youth rights in the United States Morse v. Frederick Newsboys' strike of 1899 Quebec Charter of Human Rights and Freedoms Wild in the Streets Theory/concepts Adultcentrism Adultism Ageism Democracy Ephebiphobia Fear of children Fear of youth Intergenerational equity Paternalism Social class Suffrage Taking Children Seriously Universal suffrage Unschooling Youth activism Youth suffrage Youth voice Issues Age of candidacy Age of consent Age of majority Age of marriage Behavior modification facility Child labour Children in the military Child marriage Compulsory education Conscription Corporal punishment at home at school in law Curfew Child abuse Emancipation of minors Gambling age Homeschooling Human rights and youth sport In loco parentis Juvenile delinquency Juvenile court Legal drinking age Legal working age Minimum driving age Marriageable age Minor (law) Minors and abortion Restavec School leaving age Smoking age Status offense Underage drinking in the US Voting age Youth-adult partnership Youth participation Youth politics Youth voting United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child Americans for a Society Free from Age Restrictions Human Rights and Youth Rights Commission National Youth Rights Association One World Youth Project Queer Youth Network Students for a Democratic Society Freechild Project Three O'Clock Lobby Youth International Party Youth Liberation of Ann Arbor Young Communist League of Canada Persons Adam Fletcher (activist) David J. Hanson David Joseph Henry John Caldwell Holt Alex Koroknay-Palicz Lyn Duff Mike A. Males Neil Postman Sonia Yaco Related Animal rights Anti-racism Direct democracy Egalitarianism Feminism Libertarianism Students rights Youth rights Society portal v t e Juvenile delinquency, also known " juvenile offending ", is the act of participating in unlawful behavior as minors (juveniles, i. e. individuals younger than the statutory age of majority). [1] Most legal systems prescribe specific procedures for dealing with juveniles, such as juvenile detention centers and courts, with it being common that juvenile systems are treated as civil cases instead of criminal, or a hybrid thereof to avoid certain requirements required for criminal cases (typically the rights to a public trial or to a jury trial). A juvenile delinquent in the United States is a person who is typically below 18 (17 in Georgia, New York, Michigan, Missouri, North Carolina, New Hampshire, Texas, and Wisconsin) years of age and commits an act that otherwise would have been charged as a crime if they were an adult. Depending on the type and severity of the offense committed, it is possible for people under 18 to be charged and treated as adults. In recent years [ vague] a higher proportion of youth have experienced arrests by their early 20s than in the past. Some scholars have concluded that this may reflect more aggressive criminal justice and zero-tolerance policies rather than changes in youth behavior. [2] Juvenile crimes can range from status offenses (such as underage smoking/drinking), to property crimes and violent crimes. Youth violence rates in the United States have dropped to approximately 12% of peak rates in 1993 according to official US government statistics, suggesting that most juvenile offending is non-violent. [3] One contributing factor that has gained attention in recent years is the school to prison pipeline. The focus on punitive punishment has been seen to correlate with juvenile delinquency rates. [4] Some have suggested shifting from zero tolerance policies to restorative justice approaches. [5] However, juvenile offending can be considered to be normative adolescent behavior. [6] This is because most teens tend to offend by committing non-violent crimes, only once or a few times, and only during adolescence. Repeated and/or violent offending is likely to lead to later and more violent offenses. When this happens, the offender often displays antisocial behavior even before reaching adolescence. [7] Overview [ edit] Juvenile delinquency, or offending, is often separated into three categories: delinquency, crimes committed by minors, which are dealt with by the juvenile courts and justice system; criminal behavior, crimes dealt with by the criminal justice system; status offenses, offenses that are only classified as such because only a minor can commit them. One example of this is possession of alcohol by a minor. These offenses are also dealt with by the juvenile courts. [8] Currently, there is not an agency whose jurisdiction is tracking worldwide juvenile delinquency but UNICEF estimates that over one million children are in some type of detention globally. [9] Many countries do not keep records of the amount of delinquent or detained minors but of the ones that do, the United States has the highest number of juvenile delinquency cases. [10] In the United States, the Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention compiles data concerning trends in juvenile delinquency. According to their most recent publication, 7 in 1000 juveniles in the US committed a serious crime in 2016. [11] A serious crime is defined by the US Department of Justice as one of the following eight offenses: murder and non-negligent homicide, rape (legacy & revised), robbery, aggravated assault, burglary, motor vehicle theft, larceny-theft, and arson. [12] According to research compiled by James Howell in 2009, the arrest rate for juveniles has been dropping consistently since its peak in 1994. [13] Of the cases for juvenile delinquency that make it through the court system, probation is the most common consequence and males account for over 70% of the caseloads. [14] [11] According to developmental research by Moffitt (2006), [6] there are two different types of offenders that emerge in adolescence. The first is an age specific offender, referred to as the adolescence-limited offender, for whom juvenile offending or delinquency begins and ends during their period of adolescence. Moffitt argues that most teenagers tend to show some form of antisocial or delinquent behavior during adolescence, it is therefore important to account for these behaviors in childhood in order to determine whether they will be adolescence-limited offenders or something more long term. [15] The other type of offender is the repeat offender, referred to as the life-course-persistent offender, who begins offending or showing antisocial/aggressive behavior in adolescence (or even in childhood) and continues into adulthood. [7] Situational Factors [ edit] Most of influencing factors for juvenile delinquency tend to be caused by a mix of both genetic and environmental factors. [16] According to Laurence Steinberg's book Adolescence, the two largest predictors of juvenile delinquency are parenting style and peer group association. [16] Additional factors that may lead a teenager into juvenile delinquency include poor or low socioeconomic status, poor school readiness/performance and/or failure and peer rejection. Delinquent activity, especially the involvement in youth gangs, may also be caused by a desire for protection against violence or financial hardship. Juvenile offenders can view delinquent activity as a means of gaining access to resources to protect against such threats. Research by Carrie Dabb indicates that even changes in the weather can increase the likelihood of children exhibiting deviant behavior. [17] Family Environment [ edit] Family factors that may have an influence on offending include: the level of parental supervision, the way parents discipline a child, parental conflict or separation, criminal activity by parents or siblings, parental abuse or neglect, and the quality of the parent-child relationship. [18] As mentioned above, parenting style is one of the largest predictors of juvenile delinquency. There are 4 categories of parenting styles which describe the attitudes and behaviors that parents express while raising their children. [19] Authoritative parenting is characterized by warmth and support in addition to discipline. Indulgent parenting is characterized by warmth and regard towards their children but lack structure and discipline. Authoritarian parenting is characterized by high discipline without the warmth thus leading to often hostile demeanor

Criminology and penology Theory Anomie Biosocial criminology Broken windows Collective efficacy Crime analysis Criminalization Differential association Deviance Labeling theory Psychopathy Rational choice Social control Social disorganization Social learning Strain Subculture Symbolic interactionism Victimology Types of crime Against humanity Blue-collar Corporate Juvenile Organized Political Public-order State State-corporate Victimless White-collar War Methods Comparative Profiling Critical theory Ethnography Uniform Crime Reports Crime mapping Positivist school Qualitative Quantitative BJS NIBRS Penology Denunciation Deterrence Incapacitation Trial Prison abolition open reform Prisoner Prisoner abuse Prisoners' rights Rehabilitation Recidivism Justice in penology Participatory Restorative Retributive Solitary confinement Schools Anarchist criminology Chicago school Classical school Conflict criminology Critical criminology Environmental criminology Feminist school Integrative criminology Italian school Left realism Marxist criminology Neo-classical school Postmodernist school Right realism Subfields American Anthropological Conflict Criminology Critical Culture Cyber Demography Development Environmental Experimental Organizational Public Radical criminology Browse Index Journals Organizations People v t e Part of the Politics series on Youth rights Activities Bailey v. Drexel Furniture Co. Child Labor Deterrence Act Children's Online Privacy Protection Act Convention on the Rights of the Child Fair Labor Standards Act Hammer v. Dagenhart History of youth rights in the United States Morse v. Frederick Newsboys' strike of 1899 Quebec Charter of Human Rights and Freedoms Wild in the Streets Theory/concepts Adultcentrism Adultism Ageism Democracy Ephebiphobia Fear of children Fear of youth Intergenerational equity Paternalism Social class Suffrage Taking Children Seriously Universal suffrage Unschooling Youth activism Youth suffrage Youth voice Issues Age of candidacy Age of consent Age of majority Age of marriage Behavior modification facility Child labour Children in the military Child marriage Compulsory education Conscription Corporal punishment at home at school in law Curfew Child abuse Emancipation of minors Gambling age Homeschooling Human rights and youth sport In loco parentis Juvenile delinquency Juvenile court Legal drinking age Legal working age Minimum driving age Marriageable age Minor (law) Minors and abortion Restavec School leaving age Smoking age Status offense Underage drinking in the US Voting age Youth-adult partnership Youth participation Youth politics Youth voting United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child Americans for a Society Free from Age Restrictions Human Rights and Youth Rights Commission National Youth Rights Association One World Youth Project Queer Youth Network Students for a Democratic Society Freechild Project Three O'Clock Lobby Youth International Party Youth Liberation of Ann Arbor Young Communist League of Canada Persons Adam Fletcher (activist) David J. Hanson David Joseph Henry John Caldwell Holt Alex Koroknay-Palicz Lyn Duff Mike A. Males Neil Postman Sonia Yaco Related Animal rights Anti-racism Direct democracy Egalitarianism Feminism Libertarianism Students rights Youth rights Society portal v t e Juvenile delinquency, also known " juvenile offending ", is the act of participating in unlawful behavior as minors (juveniles, i. e. individuals younger than the statutory age of majority). [1] Most legal systems prescribe specific procedures for dealing with juveniles, such as juvenile detention centers and courts, with it being common that juvenile systems are treated as civil cases instead of criminal, or a hybrid thereof to avoid certain requirements required for criminal cases (typically the rights to a public trial or to a jury trial). A juvenile delinquent in the United States is a person who is typically below 18 (17 in Georgia, New York, Michigan, Missouri, North Carolina, New Hampshire, Texas, and Wisconsin) years of age and commits an act that otherwise would have been charged as a crime if they were an adult. Depending on the type and severity of the offense committed, it is possible for people under 18 to be charged and treated as adults. In recent years [ vague] a higher proportion of youth have experienced arrests by their early 20s than in the past. Some scholars have concluded that this may reflect more aggressive criminal justice and zero-tolerance policies rather than changes in youth behavior. [2] Juvenile crimes can range from status offenses (such as underage smoking/drinking), to property crimes and violent crimes. Youth violence rates in the United States have dropped to approximately 12% of peak rates in 1993 according to official US government statistics, suggesting that most juvenile offending is non-violent. [3] One contributing factor that has gained attention in recent years is the school to prison pipeline. The focus on punitive punishment has been seen to correlate with juvenile delinquency rates. [4] Some have suggested shifting from zero tolerance policies to restorative justice approaches. [5] However, juvenile offending can be considered to be normative adolescent behavior. [6] This is because most teens tend to offend by committing non-violent crimes, only once or a few times, and only during adolescence. Repeated and/or violent offending is likely to lead to later and more violent offenses. When this happens, the offender often displays antisocial behavior even before reaching adolescence. [7] Overview [ edit] Juvenile delinquency, or offending, is often separated into three categories: delinquency, crimes committed by minors, which are dealt with by the juvenile courts and justice system; criminal behavior, crimes dealt with by the criminal justice system; status offenses, offenses that are only classified as such because only a minor can commit them. One example of this is possession of alcohol by a minor. These offenses are also dealt with by the juvenile courts. [8] Currently, there is not an agency whose jurisdiction is tracking worldwide juvenile delinquency but UNICEF estimates that over one million children are in some type of detention globally. [9] Many countries do not keep records of the amount of delinquent or detained minors but of the ones that do, the United States has the highest number of juvenile delinquency cases. [10] In the United States, the Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention compiles data concerning trends in juvenile delinquency. According to their most recent publication, 7 in 1000 juveniles in the US committed a serious crime in 2016. [11] A serious crime is defined by the US Department of Justice as one of the following eight offenses: murder and non-negligent homicide, rape (legacy & revised), robbery, aggravated assault, burglary, motor vehicle theft, larceny-theft, and arson. [12] According to research compiled by James Howell in 2009, the arrest rate for juveniles has been dropping consistently since its peak in 1994. [13] Of the cases for juvenile delinquency that make it through the court system, probation is the most common consequence and males account for over 70% of the caseloads. [14] [11] According to developmental research by Moffitt (2006), [6] there are two different types of offenders that emerge in adolescence. The first is an age specific offender, referred to as the adolescence-limited offender, for whom juvenile offending or delinquency begins and ends during their period of adolescence. Moffitt argues that most teenagers tend to show some form of antisocial or delinquent behavior during adolescence, it is therefore important to account for these behaviors in childhood in order to determine whether they will be adolescence-limited offenders or something more long term. [15] The other type of offender is the repeat offender, referred to as the life-course-persistent offender, who begins offending or showing antisocial/aggressive behavior in adolescence (or even in childhood) and continues into adulthood. [7] Situational Factors [ edit] Most of influencing factors for juvenile delinquency tend to be caused by a mix of both genetic and environmental factors. [16] According to Laurence Steinberg's book Adolescence, the two largest predictors of juvenile delinquency are parenting style and peer group association. [16] Additional factors that may lead a teenager into juvenile delinquency include poor or low socioeconomic status, poor school readiness/performance and/or failure and peer rejection. Delinquent activity, especially the involvement in youth gangs, may also be caused by a desire for protection against violence or financial hardship. Juvenile offenders can view delinquent activity as a means of gaining access to resources to protect against such threats. Research by Carrie Dabb indicates that even changes in the weather can increase the likelihood of children exhibiting deviant behavior. [17] Family Environment [ edit] Family factors that may have an influence on offending include: the level of parental supervision, the way parents discipline a child, parental conflict or separation, criminal activity by parents or siblings, parental abuse or neglect, and the quality of the parent-child relationship. [18] As mentioned above, parenting style is one of the largest predictors of juvenile delinquency. There are 4 categories of parenting styles which describe the attitudes and behaviors that parents express while raising their children. [19] Authoritative parenting is characterized by warmth and support in addition to discipline. Indulgent parenting is characterized by warmth and regard towards their children but lack structure and discipline. Authoritarian parenting is characterized by high discipline without the warmth thus leading to often hostile demeanor

Watch Full Length Juvenile délinquants sexuels.

Juve&n'ile De&linquents: New* Wo`r`ld. hindi dubbed watch OnLinE, Juvenile Delinquents: New World Order no registration.

Columnist John Living

Bio: NYC Actor..this is not a dress rehearsal!

????????????

https://rqzamovies.com/m16728.html

????????????

&ref(https://m.media-amazon.com/images/M/MV5BMGIyYTI1NTQtODlhYS00NzczLTg1MTgtMWNjZDYyZjUyZjlkXkEyXkFqcGdeQXVyNjM2OTI5Mzg@._V1_UX182_CR0,0,182,268_AL_.jpg) / Directed by - Neil Goss / reviews - Broken teens trying to claim somethings their parents failed to provide - A Future and Purpose / Actor - Demitra Sealy. Shop for Books on Google Play Browse the world's largest eBookstore and start reading today on the web, tablet, phone, or ereader. Go to Google Play Now ?.

Suggested Citation: "The Juvenile Justice System. " National Research Council and Institute of Medicine. 2001. Juvenile Crime, Juvenile Justice. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. doi: 10. 17226/9747. × 5 The Juvenile Justice System A separate juvenile justice system was established in the United States about 100 years ago with the goal of diverting youthful offenders from the destructive punishments of criminal courts and encouraging rehabilitation based on the individual juvenile's needs. This system was to differ from adult or criminal court in a number of ways. It was to focus on the child or adolescent as a person in need of assistance, not on the act that brought him or her before the court. The proceedings were informal, with much discretion left to the juvenile court judge. Because the judge was to act in the best interests of the child, procedural safeguards available to adults, such as the right to an attorney, the right to know the charges brought against one, the right to trial by jury, and the right to confront one's accuser, were thought unnecessary. Juvenile court proceedings were closed to the public and juvenile records were to remain confidential so as not to interfere with the child's or adolescent's ability to be rehabilitated and reintegrated into society. The very language used in juvenile court underscored these differences. Juveniles are not charged with crimes, but rather with delinquencies; they are not found guilty, but rather are adjudicated delinquent; they are not sent to prison, but to training school or reformatory. In practice, there was always a tension between social welfare and social control?that is, focusing on the best interests of the individual child versus focusing on punishment, incapacitation, and protecting society from certain offenses. This tension has shifted over time and has varied significantly from jurisdiction to jurisdiction, and it remains today. In response to the increase in violent crime in the 1980s, state legal reforms in juvenile justice, particularly those that deal with serious offenses, have stressed punitiveness, accountability, and a concern for public safety, rejecting traditional concerns for diversion and rehabilitation in favor of a get-tough approach to juvenile crime and punishment. This change in emphasis from a focus on rehabilitating the individual to punishing the act is exemplified by the 17 states that redefined the purpose clause of their juvenile courts to emphasize public safety, certainty of sanctions, and offender accountability (Torbet and Szymanski, 1998). Inherent in this change in focus is the belief that the juvenile justice system is too soft on delinquents, who are thought to be potentially as much a threat to public safety as their adult criminal counterparts. It is important to remember that the United States has at least 51 different juvenile justice systems, not one. Each state and the District of Columbia has its own laws that govern its juvenile justice system. How juvenile courts operate may vary from county to county and municipality to municipality within a state. The federal government has jurisdiction over a small number of juveniles, such as those who commit crimes on Indian reservations or in national parks, and it has its own laws to govern juveniles within its system. States that receive money under the federal Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention Act must meet certain requirements, such as not housing juveniles with adults in detention or incarceration facilities, but it is state law that governs the structure of juvenile courts and juvenile corrections facilities. When this report refers to the juvenile justice system, it is referring to a generic framework that is more or less representative of what happens in any given state. Legal reforms and policy changes that have taken place under the get-tough rubric include more aggressive policing of juveniles, making it easier (or in some cases mandatory) to treat a juvenile who has committed certain offenses as an adult, moving decision making about where to try a juvenile from the judge to the prosecutor or the state legislature, changing sentencing options, and opening juvenile proceedings and records. Changes in laws do not necessarily translate into changes in practice. In addition to the belief that at least some juvenile offenders are amenable to treatment and rehabilitation, other factors limit overreliance on get-tough measures: (1) the expense of incarceration, (2) overcrowding that results from sentencing offenders more harshly, and (3) research evidence that finds few gains, in terms of reduced rates of recidivism, from simply incapacitating youth without any attention to treatment or rehabilitation (Beck and Shipley, 1987; Byrne and Kelly, 1989; Hagan, 1991; National Research Council, 1993a; National Research Council, 1993b; Shannon et al., 1988). Practice may also move in ways not envisioned when laws are passed. For example, many jurisdictions have been experimenting with alternative models of juvenile justice, such as the restorative justice model. Whereas the traditional juvenile justice model focuses attention on offender rehabilitation and the current get-tough changes focus on offense punishment, the restorative model focuses on balancing the needs of victims, offenders, and communities (Bazemore and Umbreit, 1995). Tracking changes in practice is difficult, not only because of the differences in structure of the juvenile justice system among the states, but also because the information collected about case processing and about incarcerated juveniles differs from state to state, and because there are few national data. Some states collect and publish a large amount of data on various aspects of the juvenile justice system, but for most states the data are not readily available. Although data are collected nationally on juvenile court case processing, 1 the courts are not required to submit data, so that national juvenile court statistics are derived from courts that cover only about two-thirds of the entire juvenile population (Stahl et al., 1999). Furthermore, there are no published national data on the number of juveniles convicted by offense, the number incarcerated by offense, sentence length, time served in confinement, or time served on parole (Langan and Farrington, 1998). 2 Such national information is available on adults incarcerated in prisons and jails. The center of the juvenile justice system is the juvenile or family court (Moore and Wakeling, 1997). In fact, the term juvenile justice is often used synonymously with the juvenile court, but it also may refer to other affiliated institutions in addition to the court, including the police, prosecuting and defense attorneys, probation, juvenile detention centers, and juvenile correctional facilities (Rosenheim, 1983). In this chapter, juvenile justice is used in the latter, larger sense. After providing a brief historical background of the juvenile court and a description of stages in the juvenile justice system, we examine the various legal and policy changes that have taken place in recent years, the impact those changes have had on practice, and the result of the laws, policy, and practice on juveniles caught up in the juvenile justice system. Throughout the chapter, differences by race and by gender in involvement in the juvenile justice system are noted. Chapter 6 examines in more detail the overrepresentation of minorities in the juvenile justice system. 1 The National Center for Juvenile Justice, under contract with the Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention, U. S. Department of Justice, has collected and analyzed juvenile court statistics since 1975. 2 Data on the first two categories are already collected but not published. Data on the latter three categories are not now collected nationally. HISTORY OF THE JUVENILE JUSTICE SYSTEM Until the early 19th century in the United States, children as young as 7 years old could be tried in criminal court and, if convicted, sentenced to prison or even to death. Children under the age of 7 were presumed to be unable to form criminal intent and were therefore exempt from punishment. The establishment of special courts and incarceration facilities for juveniles was part of Progressive Era reforms, along with kindergarten, child labor laws, mandatory education, school lunches, and vocational education, that were aimed at enhancing optimal child development in the industrial city (Schlossman, 1983). Reformers believed that treating children and adolescents as adult criminals was unnecessarily harsh and resulted in their corruption. In the words of one reformer, the main reason for the establishment of the juvenile court was “to prevent children from being treated as criminals ” (Van Waters, 1927:217). Based on the premise that children and young adolescents are developmentally different from adults and are therefore more amenable to rehabilitation, and that they are not criminally responsible for their actions, children and adolescents brought before the court were assumed to require the court's intervention and guidance, rather than solely punishment. They were not to be accused of specific crimes. The reason a juvenile came before the court?be it for committing an offense or because of abuse or neglect by his or her parents or for being uncontrollable?was less important than understanding the child's life situation and finding appropriate, individualized rehabilitative services (Coalition for Juvenile Justice, 1998; Schlossman, 1983). Historians have noted that the establishment of the juvenile court not only diverted youngsters from the criminal court, but also expanded the net of social control over juveniles through the incorporation of status jurisdiction into states' juvenile codes (e. g., Platt, 1977; Schlossman, 1977). The first juvenile court in the United States, authorized by the Illinois

Watch Full Length Juvenile delinquants. YouTube. {Juvenile,Delinquents: New,World,Order,Full,Movie,2018. movierulz" WATCH ONLINE LATINPOST watch full length Watch Juvenile Delinquents: New World Order OnlIne Zstream….

Watch Full Length Juvenile délinquants.

Watch Full Length Juvenile delinquent.

Criminology and penology Theory Anomie Biosocial criminology Broken windows Collective efficacy Crime analysis Criminalization Differential association Deviance Labeling theory Psychopathy Rational choice Social control Social disorganization Social learning Strain Subculture Symbolic interactionism Victimology Types of crime Against humanity Blue-collar Corporate Juvenile Organized Political Public-order State State-corporate Victimless White-collar War Methods Comparative Profiling Critical theory Ethnography Uniform Crime Reports Crime mapping Positivist school Qualitative Quantitative BJS NIBRS Penology Denunciation Deterrence Incapacitation Trial Prison abolition open reform Prisoner Prisoner abuse Prisoners' rights Rehabilitation Recidivism Justice in penology Participatory Restorative Retributive Solitary confinement Schools Anarchist criminology Chicago school Classical school Conflict criminology Critical criminology Environmental criminology Feminist school Integrative criminology Italian school Left realism Marxist criminology Neo-classical school Postmodernist school Right realism Subfields American Anthropological Conflict Criminology Critical Culture Cyber Demography Development Environmental Experimental Organizational Public Radical criminology Browse Index Journals Organizations People v t e Part of the Politics series on Youth rights Activities Bailey v. Drexel Furniture Co. Child Labor Deterrence Act Children's Online Privacy Protection Act Convention on the Rights of the Child Fair Labor Standards Act Hammer v. Dagenhart History of youth rights in the United States Morse v. Frederick Newsboys' strike of 1899 Quebec Charter of Human Rights and Freedoms Wild in the Streets Theory/concepts Adultcentrism Adultism Ageism Democracy Ephebiphobia Fear of children Fear of youth Intergenerational equity Paternalism Social class Suffrage Taking Children Seriously Universal suffrage Unschooling Youth activism Youth suffrage Youth voice Issues Age of candidacy Age of consent Age of majority Age of marriage Behavior modification facility Child labour Children in the military Child marriage Compulsory education Conscription Corporal punishment at home at school in law Curfew Child abuse Emancipation of minors Gambling age Homeschooling Human rights and youth sport In loco parentis Juvenile delinquency Juvenile court Legal drinking age Legal working age Minimum driving age Marriageable age Minor (law) Minors and abortion Restavec School leaving age Smoking age Status offense Underage drinking in the US Voting age Youth-adult partnership Youth participation Youth politics Youth voting United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child Americans for a Society Free from Age Restrictions Human Rights and Youth Rights Commission National Youth Rights Association One World Youth Project Queer Youth Network Students for a Democratic Society Freechild Project Three O'Clock Lobby Youth International Party Youth Liberation of Ann Arbor Young Communist League of Canada Persons Adam Fletcher (activist) David J. Hanson David Joseph Henry John Caldwell Holt Alex Koroknay-Palicz Lyn Duff Mike A. Males Neil Postman Sonia Yaco Related Animal rights Anti-racism Direct democracy Egalitarianism Feminism Libertarianism Students rights Youth rights Society portal v t e Juvenile delinquency, also known " juvenile offending ", is the act of participating in unlawful behavior as minors (juveniles, i. e. individuals younger than the statutory age of majority). [1] Most legal systems prescribe specific procedures for dealing with juveniles, such as juvenile detention centers and courts, with it being common that juvenile systems are treated as civil cases instead of criminal, or a hybrid thereof to avoid certain requirements required for criminal cases (typically the rights to a public trial or to a jury trial). A juvenile delinquent in the United States is a person who is typically below 18 (17 in Georgia, New York, Michigan, Missouri, North Carolina, New Hampshire, Texas, and Wisconsin) years of age and commits an act that otherwise would have been charged as a crime if they were an adult. Depending on the type and severity of the offense committed, it is possible for people under 18 to be charged and treated as adults. In recent years [ vague] a higher proportion of youth have experienced arrests by their early 20s than in the past. Some scholars have concluded that this may reflect more aggressive criminal justice and zero-tolerance policies rather than changes in youth behavior. [2] Juvenile crimes can range from status offenses (such as underage smoking/drinking), to property crimes and violent crimes. Youth violence rates in the United States have dropped to approximately 12% of peak rates in 1993 according to official US government statistics, suggesting that most juvenile offending is non-violent. [3] One contributing factor that has gained attention in recent years is the school to prison pipeline. The focus on punitive punishment has been seen to correlate with juvenile delinquency rates. [4] Some have suggested shifting from zero tolerance policies to restorative justice approaches. [5] However, juvenile offending can be considered to be normative adolescent behavior. [6] This is because most teens tend to offend by committing non-violent crimes, only once or a few times, and only during adolescence. Repeated and/or violent offending is likely to lead to later and more violent offenses. When this happens, the offender often displays antisocial behavior even before reaching adolescence. [7] Overview [ edit] Juvenile delinquency, or offending, is often separated into three categories: delinquency, crimes committed by minors, which are dealt with by the juvenile courts and justice system; criminal behavior, crimes dealt with by the criminal justice system; status offenses, offenses that are only classified as such because only a minor can commit them. One example of this is possession of alcohol by a minor. These offenses are also dealt with by the juvenile courts. [8] Currently, there is not an agency whose jurisdiction is tracking worldwide juvenile delinquency but UNICEF estimates that over one million children are in some type of detention globally. [9] Many countries do not keep records of the amount of delinquent or detained minors but of the ones that do, the United States has the highest number of juvenile delinquency cases. [10] In the United States, the Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention compiles data concerning trends in juvenile delinquency. According to their most recent publication, 7 in 1000 juveniles in the US committed a serious crime in 2016. [11] A serious crime is defined by the US Department of Justice as one of the following eight offenses: murder and non-negligent homicide, rape (legacy & revised), robbery, aggravated assault, burglary, motor vehicle theft, larceny-theft, and arson. [12] According to research compiled by James Howell in 2009, the arrest rate for juveniles has been dropping consistently since its peak in 1994. [13] Of the cases for juvenile delinquency that make it through the court system, probation is the most common consequence and males account for over 70% of the caseloads. [14] [11] According to developmental research by Moffitt (2006), [6] there are two different types of offenders that emerge in adolescence. The first is an age specific offender, referred to as the adolescence-limited offender, for whom juvenile offending or delinquency begins and ends during their period of adolescence. Moffitt argues that most teenagers tend to show some form of antisocial or delinquent behavior during adolescence, it is therefore important to account for these behaviors in childhood in order to determine whether they will be adolescence-limited offenders or something more long term. [15] The other type of offender is the repeat offender, referred to as the life-course-persistent offender, who begins offending or showing antisocial/aggressive behavior in adolescence (or even in childhood) and continues into adulthood. [7] Situational Factors [ edit] Most of influencing factors for juvenile delinquency tend to be caused by a mix of both genetic and environmental factors. [16] According to Laurence Steinberg's book Adolescence, the two largest predictors of juvenile delinquency are parenting style and peer group association. [16] Additional factors that may lead a teenager into juvenile delinquency include poor or low socioeconomic status, poor school readiness/performance and/or failure and peer rejection. Delinquent activity, especially the involvement in youth gangs, may also be caused by a desire for protection against violence or financial hardship. Juvenile offenders can view delinquent activity as a means of gaining access to resources to protect against such threats. Research by Carrie Dabb indicates that even changes in the weather can increase the likelihood of children exhibiting deviant behavior. [17] Family Environment [ edit] Family factors that may have an influence on offending include: the level of parental supervision, the way parents discipline a child, parental conflict or separation, criminal activity by parents or siblings, parental abuse or neglect, and the quality of the parent-child relationship. [18] As mentioned above, parenting style is one of the largest predictors of juvenile delinquency. There are 4 categories of parenting styles which describe the attitudes and behaviors that parents express while raising their children. [19] Authoritative parenting is characterized by warmth and support in addition to discipline. Indulgent parenting is characterized by warmth and regard towards their children but lack structure and discipline. Authoritarian parenting is characterized by high discipline without the warmth thus leading to often hostile demeanor

Criminology and penology Theory Anomie Biosocial criminology Broken windows Collective efficacy Crime analysis Criminalization Differential association Deviance Labeling theory Psychopathy Rational choice Social control Social disorganization Social learning Strain Subculture Symbolic interactionism Victimology Types of crime Against humanity Blue-collar Corporate Juvenile Organized Political Public-order State State-corporate Victimless White-collar War Methods Comparative Profiling Critical theory Ethnography Uniform Crime Reports Crime mapping Positivist school Qualitative Quantitative BJS NIBRS Penology Denunciation Deterrence Incapacitation Trial Prison abolition open reform Prisoner Prisoner abuse Prisoners' rights Rehabilitation Recidivism Justice in penology Participatory Restorative Retributive Solitary confinement Schools Anarchist criminology Chicago school Classical school Conflict criminology Critical criminology Environmental criminology Feminist school Integrative criminology Italian school Left realism Marxist criminology Neo-classical school Postmodernist school Right realism Subfields American Anthropological Conflict Criminology Critical Culture Cyber Demography Development Environmental Experimental Organizational Public Radical criminology Browse Index Journals Organizations People v t e Part of the Politics series on Youth rights Activities Bailey v. Drexel Furniture Co. Child Labor Deterrence Act Children's Online Privacy Protection Act Convention on the Rights of the Child Fair Labor Standards Act Hammer v. Dagenhart History of youth rights in the United States Morse v. Frederick Newsboys' strike of 1899 Quebec Charter of Human Rights and Freedoms Wild in the Streets Theory/concepts Adultcentrism Adultism Ageism Democracy Ephebiphobia Fear of children Fear of youth Intergenerational equity Paternalism Social class Suffrage Taking Children Seriously Universal suffrage Unschooling Youth activism Youth suffrage Youth voice Issues Age of candidacy Age of consent Age of majority Age of marriage Behavior modification facility Child labour Children in the military Child marriage Compulsory education Conscription Corporal punishment at home at school in law Curfew Child abuse Emancipation of minors Gambling age Homeschooling Human rights and youth sport In loco parentis Juvenile delinquency Juvenile court Legal drinking age Legal working age Minimum driving age Marriageable age Minor (law) Minors and abortion Restavec School leaving age Smoking age Status offense Underage drinking in the US Voting age Youth-adult partnership Youth participation Youth politics Youth voting United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child Americans for a Society Free from Age Restrictions Human Rights and Youth Rights Commission National Youth Rights Association One World Youth Project Queer Youth Network Students for a Democratic Society Freechild Project Three O'Clock Lobby Youth International Party Youth Liberation of Ann Arbor Young Communist League of Canada Persons Adam Fletcher (activist) David J. Hanson David Joseph Henry John Caldwell Holt Alex Koroknay-Palicz Lyn Duff Mike A. Males Neil Postman Sonia Yaco Related Animal rights Anti-racism Direct democracy Egalitarianism Feminism Libertarianism Students rights Youth rights Society portal v t e Juvenile delinquency, also known " juvenile offending ", is the act of participating in unlawful behavior as minors (juveniles, i. e. individuals younger than the statutory age of majority). [1] Most legal systems prescribe specific procedures for dealing with juveniles, such as juvenile detention centers and courts, with it being common that juvenile systems are treated as civil cases instead of criminal, or a hybrid thereof to avoid certain requirements required for criminal cases (typically the rights to a public trial or to a jury trial). A juvenile delinquent in the United States is a person who is typically below 18 (17 in Georgia, New York, Michigan, Missouri, North Carolina, New Hampshire, Texas, and Wisconsin) years of age and commits an act that otherwise would have been charged as a crime if they were an adult. Depending on the type and severity of the offense committed, it is possible for people under 18 to be charged and treated as adults. In recent years [ vague] a higher proportion of youth have experienced arrests by their early 20s than in the past. Some scholars have concluded that this may reflect more aggressive criminal justice and zero-tolerance policies rather than changes in youth behavior. [2] Juvenile crimes can range from status offenses (such as underage smoking/drinking), to property crimes and violent crimes. Youth violence rates in the United States have dropped to approximately 12% of peak rates in 1993 according to official US government statistics, suggesting that most juvenile offending is non-violent. [3] One contributing factor that has gained attention in recent years is the school to prison pipeline. The focus on punitive punishment has been seen to correlate with juvenile delinquency rates. [4] Some have suggested shifting from zero tolerance policies to restorative justice approaches. [5] However, juvenile offending can be considered to be normative adolescent behavior. [6] This is because most teens tend to offend by committing non-violent crimes, only once or a few times, and only during adolescence. Repeated and/or violent offending is likely to lead to later and more violent offenses. When this happens, the offender often displays antisocial behavior even before reaching adolescence. [7] Overview [ edit] Juvenile delinquency, or offending, is often separated into three categories: delinquency, crimes committed by minors, which are dealt with by the juvenile courts and justice system; criminal behavior, crimes dealt with by the criminal justice system; status offenses, offenses that are only classified as such because only a minor can commit them. One example of this is possession of alcohol by a minor. These offenses are also dealt with by the juvenile courts. [8] Currently, there is not an agency whose jurisdiction is tracking worldwide juvenile delinquency but UNICEF estimates that over one million children are in some type of detention globally. [9] Many countries do not keep records of the amount of delinquent or detained minors but of the ones that do, the United States has the highest number of juvenile delinquency cases. [10] In the United States, the Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention compiles data concerning trends in juvenile delinquency. According to their most recent publication, 7 in 1000 juveniles in the US committed a serious crime in 2016. [11] A serious crime is defined by the US Department of Justice as one of the following eight offenses: murder and non-negligent homicide, rape (legacy & revised), robbery, aggravated assault, burglary, motor vehicle theft, larceny-theft, and arson. [12] According to research compiled by James Howell in 2009, the arrest rate for juveniles has been dropping consistently since its peak in 1994. [13] Of the cases for juvenile delinquency that make it through the court system, probation is the most common consequence and males account for over 70% of the caseloads. [14] [11] According to developmental research by Moffitt (2006), [6] there are two different types of offenders that emerge in adolescence. The first is an age specific offender, referred to as the adolescence-limited offender, for whom juvenile offending or delinquency begins and ends during their period of adolescence. Moffitt argues that most teenagers tend to show some form of antisocial or delinquent behavior during adolescence, it is therefore important to account for these behaviors in childhood in order to determine whether they will be adolescence-limited offenders or something more long term. [15] The other type of offender is the repeat offender, referred to as the life-course-persistent offender, who begins offending or showing antisocial/aggressive behavior in adolescence (or even in childhood) and continues into adulthood. [7] Situational Factors [ edit] Most of influencing factors for juvenile delinquency tend to be caused by a mix of both genetic and environmental factors. [16] According to Laurence Steinberg's book Adolescence, the two largest predictors of juvenile delinquency are parenting style and peer group association. [16] Additional factors that may lead a teenager into juvenile delinquency include poor or low socioeconomic status, poor school readiness/performance and/or failure and peer rejection. Delinquent activity, especially the involvement in youth gangs, may also be caused by a desire for protection against violence or financial hardship. Juvenile offenders can view delinquent activity as a means of gaining access to resources to protect against such threats. Research by Carrie Dabb indicates that even changes in the weather can increase the likelihood of children exhibiting deviant behavior. [17] Family Environment [ edit] Family factors that may have an influence on offending include: the level of parental supervision, the way parents discipline a child, parental conflict or separation, criminal activity by parents or siblings, parental abuse or neglect, and the quality of the parent-child relationship. [18] As mentioned above, parenting style is one of the largest predictors of juvenile delinquency. There are 4 categories of parenting styles which describe the attitudes and behaviors that parents express while raising their children. [19] Authoritative parenting is characterized by warmth and support in addition to discipline. Indulgent parenting is characterized by warmth and regard towards their children but lack structure and discipline. Authoritarian parenting is characterized by high discipline without the warmth thus leading to often hostile demeanorWatch Full Length Juvenile délinquants sexuels.

Juve&n'ile De&linquents: New* Wo`r`ld. hindi dubbed watch OnLinE, Juvenile Delinquents: New World Order no registration.

Columnist John Living

Bio: NYC Actor..this is not a dress rehearsal!

コメントをかく